Reviewed by Bradley G. Green

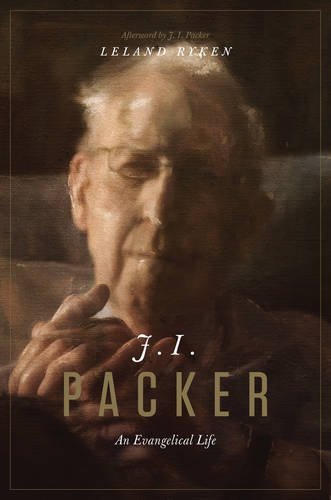

Like many readers I try to turn to biographies and autobiographies at least periodically. Last Christmas (2014) it was Thomas Oden’s wonderful autobiography, A Change of Heart: A Personal and Theological Memoir (IVP, 2014). This Christmas (2015) it was Leland Ryken’s biography of J.I. Packer: J.I. Packer: An Evangelical Life.

This is now the second biography of Packer, the first being Alister McGrath’s J.I. Packer: A Biography, published by Baker Books in 1997, almost twenty years ago. Ryken does not see his work competing with McGrath’s, and happily refers to it as source in his own biography. Ryken is clear that he is writing a biography and not a history. Ryken’s goal is “to enable readers to know J.I. Packer and to get a picture of his varied roles and accomplishments” (p. 10). A second biography does not seem in the least bit inappropriate. Packer is due to turn ninety in 2016.

Ryken writes as one with significant theological and scholarly overlap with Packer. In particular, both Packer and Ryken have spent much of their careers reading, studying, and writing on the Puritans. For example, Packer wrote A Quest for Godliness: The Puritan Vision of the Christian Life (Crossway, 1990), while Ryken wrote Worldly Saints: The Puritans as They Really Were (Zondervan, 1990), with a Foreword by J.I. Packer.

Ryken chose to structure his biography in a tripartite way.

Part I: “The Life” (164 pages)

Part 2: “The Man” (60 pages)

Part 3: “Lifelong Themes” (169 pages)

This leads to occasional small overlaps of material, but never in a way that seems unduly repetitive.

As many readers will likely have some awareness of the last half or so of Packer’s teaching, speaking, writing, and scholarly life, it is perhaps the case that the history of the first part of Packer’s life will be most illuminating. Packer’s early childhood; his injury to the head as a young boy, that he saw himself as “all churned up” as a young man; his time at Oxford where he was converted; that he studied classics major and hence knows both Latin and Greek; that he was raised Anglican and has never ultimately ceased being Anglican—indeed quite the contrary.

Readers will also learn of Packer’s service at Oak Hill College (a theological college in north London), his time at Tyndale Hall (Bristol), Latimer House (Oxford), and back to Tyndale Hall. Readers see a Packer who is a passionate champion of Evangelical positions within Anglicanism. Readers will read of Packer’s association with D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones, the Puritan Conference, they led, and the eventual split with Lloyd-Jones. Readers will learn that Packer early on established himself as a leader amongst conservative Anglicans and non-conformist Evangelicals in the UK, and that his departure to Canada to teach at Regent College was interpreted as a significant loss to the Evangelical cause in the UK.

Readers will also learn that Packer has had a long association with the magazine Christianity Today (almost since its founding in 1956), and that he eventually served as “contributing editor,” and ultimately serving as a sort of “theological advisor” to the magazine (p. 170). Although a dogged Puritan and Reformed theologian, readers learn of Packer’s contribution to the Charles Colson and Richard John Neuhaus-led initiative, Evangelicals and Catholics Together. Interestingly, readers learn that Packer views his contribution to the publication of the English Standard Version Bible to be perhaps “the most important thing that I have ever done for the Kingdom” (p. 167).

Evaluation

For this reader, Ryken’s J.I. Packer was a joy to read. As a long-time appreciative reader of Packer, it was a meaningfully and edifying read. I even learned that Ryken and I share something: we both read Packer’s ‘Fundamentalism’ and the Word of God early on in our respective theological formation and development.

Rather than summarize the contents in great detail, let me suggest four themes that struck me as I read the book.

First, I was struck that Packer had labored so long and hard on a variety of fronts. Packer has served in pastoral ministry (although local church ministry per se has not been—in terms of weekly work-load, where he has labored most), he has been a teacher, writer, speaker, and advocate for Evangelical causes both inside and outside his Anglican ecclesial home.

Packer has served as professor in a variety of places, and also as Warden at Latimer House in Oxford. During this latter appointment much of his time was taken up with extensive administrative duties, while also speaking and writing on behalf of the Evangelical faith—particularly in relationship to various challenges and skirmishes within the Church of England.

He was also an active participant in the International Council on Biblical Inerrancy, as well as Evangelicals and Catholics Together. In addition to trying to serve as pastor, academic, and administrator, Packer has served in cross-denominational efforts that he saw worthy of his time.

Second, it was intriguing to read of the various controversies throughout Packer’s life. Although Ryken never pictures Packer as overly contentious, Packer does emerge as someone who did not run from controversy. Packer could even comment that controversy served to heighten his own thinking and writing skills: he thrived intellectually when controversy was afoot. Some of the controversy was related to traditional divides between conservatives and liberals within Anglicanism. And this continued on after the move to Canada—with Packer eventually leaving his Anglican communion in Canada after that particular segment of Anglicanism fully endorsed the theological and moral legitimacy of homosexuality. He has since associated with the Anglican Church in North America (ACNA).

But, it is perhaps not the controversy between conservatives and liberals within Anglicanism which is most interesting. It is likely the controversy with D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones and non-conformist Evangelicals more generally which is so intriguing (and ultimately more sad) to read about. This controversy is now virtually the stuff of legend. And Ryken has chosen—probably wisely—to treat it without being overly sensational or sordid.

The short version is that Lloyd-Jones suggested that it was time for true Evangelicals to depart from the Church of England. This suggestion, or call, took place in 1966 at the Second National Assembly of Evangelicals. John Stott and Packer dissented. Interestingly, Ryken suggests that as important as this conflict was (and he even suggests Packer’s stated recollection of Lloyd-Jones’s comments are not exactly correct, p. 387-88), it was actually Packer’s collaboration on the book Growing into Union which was more significant. In this book, two Evangelical Anglicans and two Anglo-Catholic Anglicans collaborated to state their joint case in opposition to a proposed Anglican-Methodist merger. Ryken suggests it was the publication this book—which some Evangelicals took to be theologically suspect—which was the bigger problem.

Third, it was particularly interesting to read that a number of British Evangelicals lament that Packer never wrote a great systematic theology. D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones voiced this concern a number of years, wishing Packer had chosen to write his great systematic theology in the “Warfield tradition.” Others like Gerald Bray and Carl Trueman have given voice to this lament. Bray at one point wrote: “What we were looking for was a new Charles Hodge . . . , but what we got was Knowing God” (p. 349). Trueman wrote: “only a brilliant mind could write deep theology in such a profoundly simple way; yet he should have given us much more” (p. 350). Some readers may learn for the first time that apparently Packer has an approximately thirty year-old contract with Tyndale House Publishers to write a systematic theology. Ryken reports that the project is not actually dead. Indeed, “Packer is making progress on the book” (p. 351).

Fourth and finally, and on a personal note, I took one special insight away from the book. Packer has a special talent for summarizing material in didactically helpful ways. That is, he has a knack for presenting or packaging meaty theological material when he speaks or writes. As I read the book, I did indeed reflect upon the importance of taking difficult theological material and—at least in certain settings and circumstances—being willing and able to summarize, categorize, and present the material in ways which at least many people can understand.

Ryken repeatedly in his book commends Packer for writing “mid-level” scholarship, although Ryken also repeatedly states that Packer certainly can write more technical theological prose. But nonetheless, Ryken praises Packer for in general writing theology at a “popular” level. The Brays and Truemans and Lloyd-Jones may be right—perhaps Packer should have already written the great systematic theology (and/or, one might say, more academic theological writing). This may be. But, one can hold such a position, and still learn from his ability to communicate weighty theological material to a broad audience.

For those wanting to understand one of the most significant Evangelical writers and thinkers of the 20th century, Ryken’s volume is a great read. I suspect most readers will be encouraged and challenged, and will either return to well-worn copies of Packer on the shelves, or pick up volume they have not read yet. Ryken is to be commended for this labor. As I look back at my copy of McGrath’s J.I. Packer, and peruse my copy and re-read items I had highlighted some eighteen years ago, it is also certainly worthy of attention. Ryken has done a wonderful job of bringing the significant story of J.I. Packer up to date.

Bradley Green is Associate Professor of Christian Thought and Tradition at Union University and Review Editor for Systematic Theology here at Books At a Glance.