A Brief Book Summary from Books At a Glance

Friedrich A. von Hayek was a young economist from Vienna who joined the London School of Economics in 1932, where he remained until after World War II. Hayek experienced the move from socialism to totalitarianism in Germany and the economic trends that led to the state of affairs. He began speaking, teaching, and writing against the socialist trends in Britain, but he was not well received. The majority opinion was that National Socialism in Germany was a capitalism reaction against socialism, which painted capitalism as the villain and socialism as the solution to society’s ills (5). Most agreed that “scientific planning was necessary if Britain was to survive” (8, emphasis original).

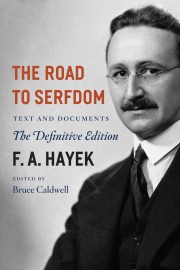

During the war, Hayek offered to help the British government with propaganda aimed at the German masses, but he was denied. So he continued at his teaching post. But he was afraid that the centralized war economy of Britain would be continued under the influence of socialists after the war. The Beveridge Report (1942), which sold about half a million copies, laid out the socialist goals for after the war. Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom sought to reverse these trends by making the economic and moral case against socialist planning, while also reminding the British of their political liberal heritage, which collectivist, central economic planning would destroy (“liberal” in this context refers to political liberalism, which values liberty for the individual over coercion from the government).

While The Road to Serfdom sold some thousands of copies in Britain, Hayek was rejected by three American publishers because his ideas were out of step with contemporary socialist trends. Finally, the University of Chicago Press published it with some edits to include America in the purview of the book. But it was really the Reader’s Digest version that popularized the book, along with a cartoon edition in the February 1945 version of Look magazine. These condensed versions gave rise to many misunderstandings in Hayek’s positions, which are nuanced throughout the book, but it led to the mass popularity of the book, which has now seen over 350,000 copies sold since its publication in 1944 (1). We offer this summary for our readers because of both its historical significance and its contemporary relevance.

Introduction

America and England are in this day (that is, Hayek’s day) following in the path of the German socialism that led to Hitler’s totalitarian state (58). Socialism has become one of the most popular economic philosophies of the time: “Scarcely anybody doubts that we must continue to move toward socialism, and most people are merely trying to deflect this movement in the interest of a particular class or group” (59). Before the war, many were even recommending Hitler’s policies. This danger of repeating Germany’s socialist experiment is the main concern of this book.

Chapter 1

The Abandoned Road

The trend toward socialism is an “entire abandonment of the individualist tradition which has created Western civilization” (73). Individual liberalism stretches back to the likes of Cicero, through the Renaissance, flourished in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, and peaked at the beginning of the twentieth century, when “the working-man in the Western world had reached a degree of material comfort, security, and personal independence which a hundred years before had seemed scarcely possible” (70).

It was the slow success of liberalism that became its decline. The masses became accustomed to the progress such that they forgot it was liberalism that produced it, and they impatiently sought to rid society of the evils that remained. Opinion became that man must not rework the old machine but create a new one, remodeling all of society to create pure freedom (72). It was the ideas of Germany that, beginning with Hegel and Marx, began to be imported into liberal countries and promise the hope of pure freedom.

Chapter Two

The Great Utopia

Socialism promises greater freedom than liberalism, but it is a false utopia. Tocqueville had noted already in 1848 that democracy seeks equality in liberty, while socialism seeks equality in restraint and servitude (77). The main difference is the idea of freedom. In liberalism, freedom has always meant freedom from the coercive powers of other men and the government, while in socialism, freedom means freedom from necessity of choice by the coercive restraint of individuals’ range of choices (77).

[To continue reading this summary, please see below....]The remainder of this article is premium content. Become a member to continue reading.

Already have an account? Sign In