An Author Interview from Books At a Glance

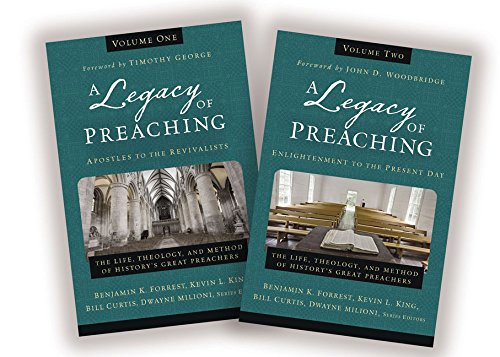

When a work like this comes around we just have to give it notice. I’m Fred Zaspel with Books At a Glance, and I’m talking about the new two-volume work, A Legacy of Preaching, from Zondervan. We have two of the editors with us to talk about their work – Benjamin Forrest and Dwayne Millioni.

Ben, Dwayne, welcome! And congratulations on such a major accomplishment!

Forrest & Millioni:

Thank you, Fred.

Zaspel:

This is your first time with us, so maybe each of you can introduce yourself to our listeners – maybe tell us what you teach and where, and maybe tell us about any other ministry you’re involved in.

Millioni:

I am the assistant professor of preaching at Southeastern Seminary in Wake Forest. I also direct the PhD program in preaching here. That’s my more than part-time job. I’m also the lead pastor of Open Door Church in Raleigh, North Carolina. And I’m also the chairman of a church planting network called the Pillar Church Planting Network. So, currently those are the three hats other than dog watcher, chief dishwasher, at home.

Forrest:

Right now, I’m an associate Dean at Liberty University. When the project started my role was as a department chair in the School of Divinity there. Through some organizational changes in the University, here, I took a promotion but it took me into a different field of the University so I’m no longer in Divinity, but in the College of Arts and Sciences. So, I’ve kind of moved around but I really like to have as much of a touch back to my roots, I guess, in the school of Divinity in the seminary. It’s been a fun project and it has spanned over a season of our lives.

Zaspel:

Okay, give us an overview of what this book is all about. What is it you are aiming to accomplish?

Forrest:

Well, the book kind of had a process of how it came to be. When I was a department chair for pastoral studies, we talked about helping students develop a particular theology of preaching, theology of Christian education, what does Scripture say to these practical ministries. So, as I assigned those, and other faculty assigned those, I realized, what has this looked like in the lives of those who have gone before? That question kept coming back to me because I think examples give us pictures of how it’s done well. The idea of the book is to survey preachers, great preachers, from a wide variety of denominational and theological perspectives, from different eras and different contexts, to examine and explore. How did they approach the task of preaching? Was there a theology that motivated this with their theology – a theology of preaching – that was honed in particular? Or was their theology a theology for preaching, where they had these theological passions and they wanted to communicate them? It was more of these overarching themes, Christology and Soteriology, and they wanted to communicate it well, so it was a theology for preaching. So that’s how this project came to be, in that we met together and we started asking who presents a good picture for the wide varieties of men and women who have gone to the Word, to take the Word to a flock who is hungry and thirsty. So that’s how it started.

Millioni:

I have been teaching courses in the history of preaching for a while and there are some very notable works. E. C. Dargan’s work is just fantastic; David Larson did a great work; and then Hughes Oliphant Old, I don’t know if anybody will ever come close to that amazing work. But I really felt there was a new work that needed to be written. What I wanted is to see in the history of preaching, actually fewer preachers selected but more written on each preacher, because typically in these massive volumes on the history of preaching you have paragraphs or tidbits at times of these guys. And we thought, let’s just go ahead and try to give a good selection that represents the history of Christian preaching, but let’s spend more time with each guy and let’s actually try to find a scholar who really knows this individual to give a thorough biographic study, his theology of preaching and methodology. I just want to tell you that Ben is really the bulwark here. He did a great job constantly looking, calling, and connecting us with some really excellent scholars. We have as many scholars in this series in Europe as we do in the US, so I was very pleased with that.

Zaspel:

Who is your intended audience? Preachers, church historians, or both?

Forrest:

A little bit of both. When I was just starting out, dabbling with the idea of trying to write, I had this idea that I thought was awesome and I told somebody, “this book’s for everybody.” And someone wisely said, “well, a book for everybody is a book for nobody.” So, as we honed what our purpose was, I really think that we came down to three ways and three types of people that will benefit strongly. I think students will benefit. So, if you’re a student going into seminary, going into pastoral ministry, going to Bible college, I think you will benefit. And I think the reason students will benefit is because our hope in this book, and in these chapters, was to present to them someone that they can spend their lives looking at as an example. None of these preachers are perfect, but we all know that John Piper was heavily influenced by Jonathan Edwards. And we see that in his work; we see that in his writing; we see that his appreciation. George Whitfield was inspired by Matthew Henry. And so, great preachers and great exegetes of the past inspired those of us today. So I want to give students people to look at for encouragement and for edification and for their own pastoring of their heart.

The second thing we wanted to do is we really wanted to equip faculty. We all teach, Kevin, Bill, Dwayne and I, we all teach in different areas, and different universities and seminaries. And we wanted to give faculty a useful resource that could be assigned in a wide variety of ways: as a main textbook, walking through the history of preaching; as a supplementary textbook, walking through the history of preaching; as a church history book, so you could kind of contextualize your study of church history through the great pulpiteers of the past.

Then, also, I think of the pastor who has been in ministry and is hitting a point where they want to either (a) grow or (b) be mentored. They are looking at some of these sage voices because in their own pastoral ministry they need the encouragement of the past to push them forward through a season of challenge and difficulty. So those are the three types of people that I had in mind.

Millioni:

I would agree. I think we all had those types of audiences in our minds. For me, I would say primarily the pastor who just wants to be encouraged in his preaching and the student who wants to study the history of it.

Zaspel:

What led you to select the specific preachers we have in the book? Fame? Effectiveness in their own day? Their lasting interest and impact? What?

Forrest:

Good question; it was a little bit of all of that. I think the first conversation I had about the book, I had it with Bill, and we were out to breakfast at Cracker Barrel. I said, “hey, I’ve got this idea, I think there’s something interesting here, what do you think?” So I pitched Bill and he asked questions but didn’t seem all that excited. I was like, “Bill, this is a great idea.” But the more we talked, the more I think he started to catch what it was and how it was different from what’s been done in the past. We left that conversation and shortly thereafter he emailed me and was like, “I think it’s a great idea; we should do it.” So something between breakfast and his email had clicked and been caught in this picture. I didn’t know Dwayne at the time, but Dwayne and Bill are good friends, they both work with the Pillar Church Planting Network and they’ve been friends for a long time. And so Bill said we’ve got to bring my friend Dwayne in on this project. He’s got a passion for this topic; he’s got students that he needs resources like this for, so he would think like a professor who would use it in the classroom; he can contribute some chapters.

Then I think the first time all four of us met was for pizza a couple of months later. We sat over pizza and I pulled out my computer and pulled out an Excel spreadsheet and we just started typing down names. I think we probably got it to ninety names and then as it got to ninety, we thought maybe this was getting too big, so who do we have to have and who can we start cutting? So we started just working it back and forth and as we would cut a couple, then we would remember somebody that needed to be in there. The list that we have is not perfect. I think it’s a great summary of people who have contributed and contributed well. But there’s probably people that maybe we should have added.

It’s not just fame driven. We wanted to have people of different regional pull, wanted to have people of different denominational pull, different eras. We didn’t want to have one era to overwhelm the other, but obviously if we’re looking at the history of preaching, our closest past is going to be very much a priority to us. Volume 1 covers about eighteen hundred years, and volume 2 covers about two hundred years. So that’s how it came to be. It was a fun process to kind of wax and wane with that.

Zaspel:

Well, I’ll agree it was a great idea.

Okay, let’s try for some general observations, although it may help to give some specific examples. One of the topics you take up for each selected preacher is his theology of preaching. Are there some general observations you can make here? Any common themes that stand out? Any mistaken notions?

Milioni:

Yes, I think so. I think we can say that every preacher in this series truly believed that they were proclaiming the Christ of the Scriptures to the glory of God and his Gospel. I think they would say that. One of the challenges, really, of the series, for me is not liking some of these preachers, and not liking or agreeing with their theology or their methodology, and yet trying to be honest if they did make a legitimate contribution. I remember editing several of these chapters and the author had done a great job and as I was reading, I would go, hmmm, I don’t like this; hmmm we should change this. (laughing) I mean all of these preachers believed that what they were doing was what they were supposed to be doing. I would also say that one of the things that I realized in working through all of these preachers is it’s hard to be stereotypical once you really dig into a preacher’s life, theology and methodology. You know, like when I was in seminary, I was taught there’s such a difference, like a 180° difference, between Origen’s preaching and Chrysostom’s preaching. Chrysostom was a Bible guy, he only preached the text of Scripture; Origen was allegorical, he was the most dangerous preacher ever; you know, that type of thing. And then when you realize, yes, they all did allegory to some extent and there are some homilies that Origen did that are pretty solid and even Perkins promoted allegory to some extent. So you can see some themes that in a more superficial study of the history of preaching we tend to be more stereotypical, I think, than what the reality was. So those were actually, for me, good to see that maybe there’s not such a stark distinction between all of these guys. Although there are definitely some clear specifics that stand out.

Zaspel:

Did these men often speak of their theology of preaching as such, or were they just concerned with the theology they had to preach? That’s a careful distinction, but I often find that preachers have not thought about the theology of preaching, as such.

Millioni:

That’s a very astute question. I don’t think they have. And that was another reason for this book. Because in the other histories of preaching there’s a lot less on their theology. Let me just say this: on the more conservative evangelical histories of preaching there’s less on the theology. There actually is more in some of the more moderate to liberal authors. So, I really wanted that in there, but I would agree with you. I think that they are more concerned with the theology you said they had to preach, which is true, for some; but then for others it was the theology that they felt like they had come to believe and preach. So for a Luther or a Chrysostom or an Augustine there was some breakthrough theology there that they came to know and love, even contra the common theology of the day, where there’s others like Savanarola, who is definitely preaching Roman Catholic theology, just doing it with passion and zeal. So I would say that they were more concerned with the theology that they had or felt like they needed to preach, as opposed to just saying what is my theology of preaching. Which, then, hopefully as a result of this study, a preacher will say what is my theology of preaching? And let that form my methodology.

Zaspel:

Luther is a big one with a theology of preaching and the theology of the preached Word, but that’s unusual, isn’t it?

Millioni:

Yes, it is. When you get Luther or Perkins who are thinking about those matters, prior.

Zaspel:

You also analyze the method of preaching. I imagine you found a wide variety there – is that right? Tell us about that.

Millioni:

Oh, definitely. And I would say again that the method was culturally bound, for the most part, and then you just had these breakthroughs. You’re going to have simple homilies through the period of the early church. You’re going to have the heavy use of the allegorical method throughout the early church, all the way up through the Reformation period. But then there is some breakthroughs and Luther and the reformers are breaking through with a methodology that is really geared towards the person, the congregation that they’re preaching to. They want to teach the Bible to their people; they want to teach theology to their people. The Puritans become this… Everyone loves the Puritans, but in the history of preaching it was such a small era. You’re talking several decades as compared to several thousand years. But I think the drastic change in their methodology is one of the things that’s so interesting to everybody about that. This plain preaching style, which the word plain, like the word Puritan, is derogative, it was meant to be sort of a sarcastic statement. We’re endeared to it because they were very passionate and very rhetorical, but plain was just meaning, hey, let’s just give them the Bible. We can still do it effectively and rhetorically with eloquence, but we are not going to just develop these lengthy sermons that are more concerned about prose and eloquence than the truths of the Scripture. There were some definite methodological changes that stuck; but culture also, I think, played in a lot to that, especially as you move into the latter couple of centuries where we’re going to see even the way they did church differently. And so the sermon takes on a different form in the nineteenth century than it did prior in the century.

Zaspel:

What are some of the more outstanding contributions to preaching made by these in your book?

Millioni:

On the one hand I would want to say that the preachers all contributed significantly because they made the cut and the few that we actually chose here. It hasn’t been until the twentieth century that we separated theology from preaching. So all of the great theologians were preachers up until the twentieth century. Now you can be a theologian and not a preacher. You can be a Bible scholar, but not a pastor, you know what I’m saying? But that was never the case. So, Augustine was an amazing preacher, but we only know him as a theologian. Well, he was; but they weren’t divorced from each other.

Zaspel:

That’s a great observation.

Millioni:

Calvin was an amazing New Testament scholar, but he was a preacher and his Institutes were for his church members. So I would say that the contribution that we all know from most of these guys really came about in their preaching. They are not writing systematic theology books. So in that sense, the answer is inherent. But then you just have some shining light.

Zaspel:

One contribution would be the Puritans that you mentioned earlier, their plain preaching.

Millioni:

Yes, I think that the Puritans finally centralized the preached word in the worship of the church. They did something to the entire liturgy that hadn’t been done since the early church. And so some of these dynamics have come about, even preaching in the common vernacular. When Huss starts preaching, not in Latin, I mean these are dramatic changes. So there are some wonderful contributions, I think.

Forrest:

One of the things, to that end, that I enjoyed was seeing the influences of others on the preachers of the chapter. And just being reminded how much we are standing on the shoulders of those who have come before us and being encouraged by that. Reading the modern preachers and seeing how they were formed and fashioned by those that they read in their use and in their young adulthood and their heroes of the faith. I think, practically, going forward I think that’s a contribution just to enjoy and appreciate as we also are challenged to stand upon those shoulders of those who have come before us.

Zaspel:

I’ve got to ask you guys each. This is very subjective and all that, but having read all of the samples, at least, from all these different preachers and looked at them, the ones through history, tell me your favorite preacher. Can you do that? I don’t care if it’s just one you’ve read or one you’ve heard from the past or from the present or one of each, tell us your favorite preacher.

Millioni:

I would say Alexander McLaren. I just feel like he was the one preacher in history, to me, that epitomizes expository preaching where he allows the Word of God to come out in his preaching. He allows the Scriptures to both form his text and even the style in which he preaches. You want to say a Spurgeon, you want to say a Whitfield, but I think I’m going to go with McLaren.

Forrest:

I don’t think I can narrow it down to one. But through this project, what it did for me, was it helped me appreciate more people outside of my tendencies. I’m not a preacher by trade or craft and so it really introduced me to people that I had not spent a lot of time with and I really enjoyed that. Some of the chapters that stood out to me was a chapter on Gregory the Great. It was one of the early chapters to be turned in. I really enjoyed it. I read it and I was edified and I was encouraged and then I went out and bought Gregory’s book through the St. Vladimir series that is being published, still. The chapter on Hubmaier, I thought was excellent and it brought me to his Anabaptist roots. The way the guy who wrote it, Cornelius, who wrote the chapter, traces him from his Catholic roots to his Anabaptist conclusion. I thought it was a fascinating chapter, I really enjoyed that. The chapter on Charles Simeon was one that took a long while to find an author for it and I had asked probably three or four well-known Simeon guys and they kept sending me to someone at the Simeon Trust. So I emailed Darrell Young, and Darrell said he would love to do it. And as I read that chapter, I really enjoyed being introduced to Simeon; he’s not somebody I had read before, so again, I went out and bought one of his books. Over and over, that happened in my own reading. This project was a long project, I mean it took several years. It was fun, though, because it was devotional. It was work, but it was devotional work. Occasionally, I would write down some edits and I’d send some stuff back, but I would type in the margin, “Amen!” I appreciated it deeply, so I don’t know if I could come up with one, but there were several chapters throughout that were just very encouraging.

Zaspel:

You talked about how this book began. Then how long were you at work on these volumes before they finally saw publication? And how many people were involved?

Forrest:

I remember getting the phone call from the publisher, that they were going to take the project on, when we were at the beach on a family vacation and I think my son was a year and a half old. He was toddling around in the waves and I got this phone call and they said they were going to take on the project and I remember going, “yes, this is awesome!” Now he’s almost ready to turn six, so it’s been four and a half years.

But it was an interesting process. We actually had the book contracted with one publisher and we went through the entire recruitment of authors, the majority of the chapters and majority of the edits. And everything was supposed to be turned in around December. So, I’m having a meeting with the publisher in September or October. It was a very small publisher and people bought into the idea of the project, but they sat down with me and asked, “how do you feel about finding a new publisher?” My stomach dropped. I’ve got sixty scholars writing, I’ve got at least fifty-two or fifty-five out of sixty chapters turned in, I think I’m months from being done and turning in the project as a full manuscript, and you want me to find a new publisher? Then they said, “we’ll do it, if you really want us to, but if you want to get out of it and you can find somebody else, go ahead.” And I just sat there, kind of dumbfounded, like this is not the direction the conversation was going. So I went back to my office and thought, okay, who can I send it to, what do I do? I don’t want to tell anybody this. So, I had some connections with some of the various Grand Rapids publishing companies and I sent it to a couple of them; I sent it to Downers Grove in Wheaton, and various places. I think all of them came back saying this is a really cool book, it’s a really interesting idea, but it’s four hundred thousand words; I don’t think I can take that on. So I started saying Lord, what am I going to do?

Millioni:

We didn’t know any of this, by the way, Fred.

Forrest:

Yeah, I’m trying to keep this close. I don’t want to cause panic. So, my Dean is walking through the back hall by my office, Dr. Hindson, and he sits down and I explained it to him and he said, “why don’t you send it to Zondervan?” And, at the time, I was thinking, I couldn’t do that, could I? He said, “I’ll send you Stan Gundry’s email address; you can just send it to Stan.” Just send it to Stan? You mean Dr. Gundry?? So, I sent it to Dr. Gundry in October and he forwarded it to somebody on his team, they got in touch with me, we talked over the phone and they said let’s meet at ETS. ETS was in the middle of November, so it all just happened really quickly that we we’re meeting with Dr. Gundry at ETS. I sat down with a couple of them and they said, “we really liked it, the sample chapters you sent were really great, the table of contents is good, we’re going to take it back to our pub board and meet on it and we’ll see if we are interested.” They went back in December and met on it and in early January they got word to me that they bought into the project. They wanted me to add a few chapters just to nuance some areas that they thought could have been added to as far as eras and such, so I think we added three or four chapters right at the end of the project. Then I could go to Dwayne and Bill and Kevin and say, “hey, guess what, guys – we got Zondervan!” Instead of passing on the panic, we got to pass on some good news.

So, it was a funny and fun process that I may not want to ever replicate.

Zaspel:

We’re talking to Ben Forrest and Dwayne Milioni, editors of the new two-volume work, A Legacy of Preaching. It’s a marvelous compendium of Christianity’s preachers and a marvelous, one-of-a-kind resource for preachers – a genuine contribution to studies in church history and a genuine contribution to those who preach. Check it out – and get a copy for your pastor!

Ben, Dwayne, thanks much for talking to us today.