An Author Interview from Books At a Glance

Greetings, I’m Fred Zaspel, and welcome to another Author Interview here at Books At a Glance. Today we talk about Biblical Hebrew with Dr. Fred Putnam co-author with Matthew Patton of Basics of Hebrew Discourse: A Guide to Working with Hebrew Prose and Poetry.

Fred, welcome, and congratulations on your new book!

Putnam:

Thank you, Fred. It was a relief to get it done. Thanks so much for talking to me about it!

Zaspel:

I have to say it brought a happy smile to my face when I saw this book coming. It brought back happy memories – if you can remember that long ago – of 30 years or so when I was a student in the seminary classroom when you taught all this. It was my first introduction to the idea of discourse analysis. I thought it was fascinating, and it was very helpful for learning to read the Hebrew Bible. I was enormously appreciative.

Putnam:

I’m glad to hear that; I really enjoyed those days.

Zaspel:

Hebrew was the initial reason I went back to seminary way back then. Tom Taylor was my first Hebrew professor – he was the older prof who had taught Hebrew for decades. Hebrew 1 was your domain then, but you were on sabbatical that semester, so I got him, and I have always been very glad for that too. But from second semester Hebrew forward it was all Putnam, and I think I’ve told you before I loved the classes, and I loved the learning.

Putnam:

I have good memories from those days.

Zaspel:

Okay, to your subject: what is discourse analysis? We’ll get to discourse analysis in the Hebrew Bible in a moment, but here just talk to us in broad terms – discourse analysis in any language. What are we talking about?

Putnam:

Discourse analysis in any language started in 1957 when a Bible translator wrote an article asking if it was possible that grammar and syntax—how words are structured and how sentences are put together—function above the level of the sentence so that paragraphs in the story, of even a novel, actually have their direction organized linguistically. He wanted to see if the sentences formed patterns and if those patterns include things like verb tenses, the length of the sentence, and the kind of clauses that are used for nominal reference for all facets of language. So, it is really the attempt to study the organization of linguistic units—or “utterances”—that are larger than a sentence.

Zaspel:

Alright now talk to us about discourse analysis in the Hebrew Bible. This can sound rather high brow and technical, so let’s begin with the big picture. What are the kinds of relationships in the text we want to keep an eye on, and then what are the “discourse markers” that identify them?

Putnam:

It helps to begin by considering an English example. Oftentimes when we tell stories, we change the tense of the verbs. For example, I was sitting at a stop-light, the light turned green, I had a feeling like I needed to wait. I did, and then a huge semi-truck comes rushing through the red light. Do you see what I did? I changed tense for effect—past to present. The same thing happens in Hebrew. Writers make certain linguistic items more prominent, or “highlight” them. We do this instinctively when we tell stories. In fact, forensic linguists were able to help catch people like the Unabomber because of their linguistic tendencies. When it comes to discourse analysis in biblical Hebrew, this same kind of thing happens—changes in verbal conjugations and clausal structures help show how the discourse fits together. But no one speaks biblical Hebrew today, so we have to pick up on these kinds of linguistic changes as non-native speakers.

We see an example of this kind of thing in Genesis 17–18, where the Bible assumes that Abraham continues to be the subject of the discourse despite a bad chapter break. Something similar occurs in 1 Samuel 3 with a series of disjunctive clauses (clauses that begin with something other than a vaw plus a verb; how Hebrew scholars describe these constructions varies tremendously), in this case, action-free clauses that signal the start of a new section and “set the scene” for what follows.

This entire discussion matters for exegesis because it helps us see how the author uses language to shape his story or poem so that the language itself helps makes the point in a way that we do not naturally see because we are not native speakers.

Zaspel:

The second half of your book deals with discourse analysis in biblical poetry. Why does this require a separate treatment? What are some of the special considerations?

Putnam:

Biblical poetry requires separate treatment for the same kinds of reasons that we treat English poetry different than English prose. We don’t read a newspaper clipping as though it were a poem and vice versa.If we read them aloud, we may even sit up straighter to read poetry because it is a different use of language.

Hebrew poetry also differs from Hebrew prose, but because the language is different, it does not act like English poetry. For example, Hebrew poetry does not rhyme whereas English poetry can. Hebrew poetry will often reuse words to make a point whereas that is considered to be bad English style. Examples of this abound throughout biblical poetry. Often these Hebrew intricacies are lost in translation because translators will try to write in good English, using different words, whereas the Hebrew writer had a point to make by using the same word repeatedly.

Zaspel:

This is really self-evident, but just to emphasize the point for preachers explain for us how an understanding of discourse analysis can be helpful in sermon preparation. Again, maybe a specific illustration or two may be helpful.

Putnam:

Exegesis is the primary concern students have, and rightly so. So, how does discourse analysis, a seemingly new topic, help with exegesis? Great question! Discourse analysis supports both exegesis and exposition because it helps us understand how a writer crafted his message to make the points he does by following the discourse clues that reveal the progress of his thought. It is not uncommon for preachers to ignore the poet’s train of thought, making points from all over a given psalm, as though their logic was better than the psalmist’s. Discourse analysis helps us align our exegesis and preaching or teaching with how the text itself is written.

Doing this means that we engage the text on its own level, before looking at commentaries. In fact, from my teaching experience, after students do this kind of work, they interact with the commentaries based on their own knowledge instead of just accepting what the commentaries say.

Zaspel:

Your book seems to be structured primarily for classroom use, but it seems to me to be very useful for individual study and review also, right?

Putnam:

The book can be helpful for anyone who even has a remote utility with Biblical Hebrew, especially because Zondervan asked both of us co-authors to present lectures that are available online. We were told specifically not to simply read the book, so that the book and lectures are complementary.

Zaspel:

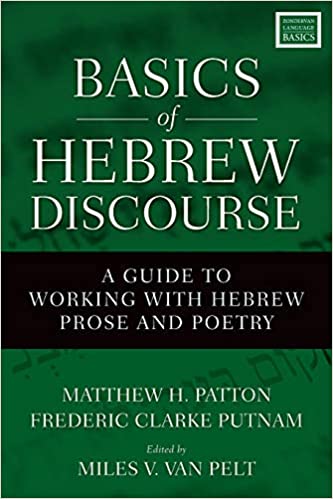

We’re talking to Dr. Fred Putnam about his new book with Matthew Patton, Basics of Hebrew Discourse: A Guide to Working with Hebrew Prose and Poetry. As I mentioned at the front, it’s been quite a number of years now, but in the seminary classroom with Fred I found all this fascinating, and I felt then that my understanding of how Hebrew works advanced considerably. If you’re not familiar with how Hebrew discourse works, this is your chance!

Fred, thanks for talking to us today.

Putnam:

Thank you so much for having me, Fred.

Buy the books

BASICS OF HEBREW DISCOURSE: A GUIDE TO WORKING WITH HEBREW PROSE AND POETRY, by Matthew Howard Patton and Frederic Clarke Putnam, edited by Miles V. Van Pelt