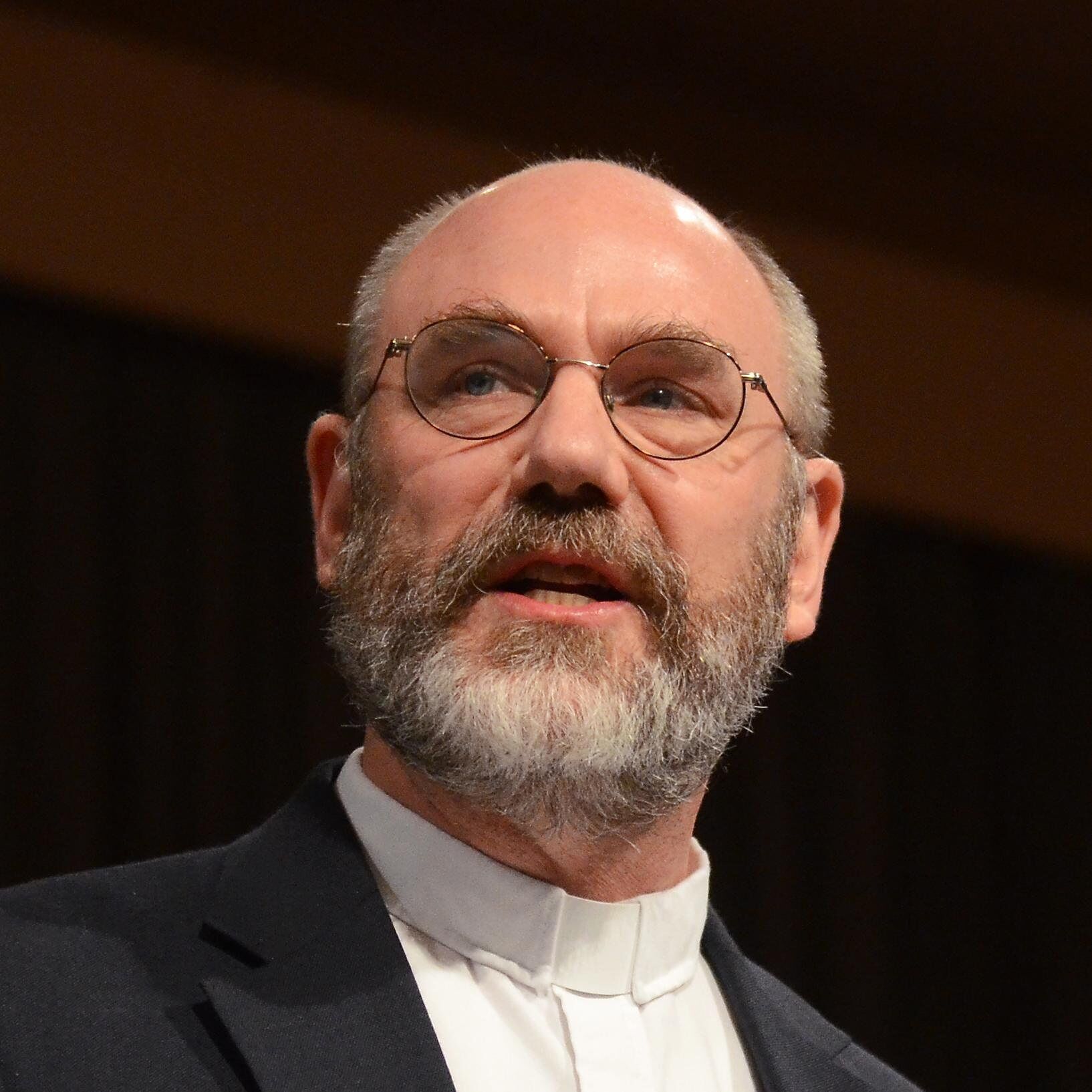

Peter Leithart’s Traces of the Trinity is an unusual book – probably unlike any you’ve read. Can you explain the doctrine of “perichoresis”? Have you even heard of it? Do you think you can see reflections of it in the created order? That is what Lethart’s unusual book is all about, and today he talks to us about it.

Books At a Glance (Fred Zaspel):

Let’s begin with the big picture: What is the doctrine of perichoresis?

Leithart:

It’s probably not technically accurate to call it a “doctrine.” Perichoresis has never been formulated by a church council. It has, however, long been a part of Christian thinking about the Trinity, as well as about the relationship of the two natures in the incarnate Christ.

It’s probably not technically accurate to call it a “doctrine.” Perichoresis has never been formulated by a church council. It has, however, long been a part of Christian thinking about the Trinity, as well as about the relationship of the two natures in the incarnate Christ.

Though the word “perichoresis” doesn’t appear anywhere in the Bible, theologians use it to designate a concept that definitely does appear. During Jesus’ prayer to His Father (John 17), He says that the Father is “in Him” and that He is “in the Father.” Jesus says the same thing earlier in John’s gospel: Don’t you know, Philip, that I am in the Father, and the Father is in Me? (John 14). That complicated, strange idea that Jesus can be in the Father who is also in Jesus – that’s perichoresis. The “mutual indwelling” or “mutual habitation” of the Persons of the Trinity. Hilary of Poitiers spoke of the Father “enveloping” the Son who also “envelops” the Father.

Think of a Mobius strip. You start on the outside, but as you move around the strip you find that you are in the inside. Inside and outside aren’t separated; each moves into the other. Perichoresis is something like that, except that the Father and Son are actually different, not “twisted” into each other to become identical.

Books At a Glance:

How is this doctrine important to our understanding of the Trinity? And why do we hear so little of it?

Leithart:

It depends on whom you are listening to. Of late, theologians have written a lot about perichoresis, so much that other theologians think that we’re hearing too much about it. I suppose there are places where no one talks about it, and maybe that’s because in those places no one talks much about the Trinity at all.

It’s important for understanding the Trinity partly because it’s part of the biblical revelation about God’s inner life. It’s one of the few things that the Bible explicitly tells us about how the Father, Son, and Spirit relate to one another. It’s important for understanding the kind of communion the Persons have with one another. Creatures are “external” to each other. Even if we were sitting next to each other, very close, there would be space between us. My body would end here, and your body would begin there. I can’t ever fully enter into another person; even in marriage, I can’t commune with another human being so closely that we become entirely one flesh. But that’s how God’s life is: The Father is so deeply engaged with, in communion with the Son that the Son is the Father’s “dwelling”; but at the same time, the Son is so much in communion with the Father that He dwells in the Father. And yet, they are irreducibly different. They are in this intimate, eternal communion, while at the same time they are distinct Persons. The Father is in the Son but never becomes the Son; the Son is in the Father, but never becomes Father. That is part of the beauty and mystery, the fascination, of the Trinity: That three Persons are utterly united and yet utterly distinct.

Maybe the most important part of this is the fact what Jesus says about the “opening” of the Triune fellowship. Father and Son dwell in one another, but then Jesus asks the Father that the disciples would be “in us,” and that the Father and Son would be “in them,” and that the disciples would be one in the same way the Father and Son are one, by dwelling in one another.

Besides, perichoresis is a fun word to say, and “perichoretic” is even better.

Books At a Glance:

Okay, then what contribution to this doctrine do you hope to make with your book. What is Traces of the Trinity all about?

Leithart:

Well, though the Triune fellowship is unique, as I said already, that same Triune God created us, the world, and everything in it. And I think that means we should expect to see the imprint of the Triune life everywhere. Theologians have thought for a long time that there are “traces” or vestiges of the Trinity within creation. I’m following in that tradition.

Books At a Glance:

Can you give us a sample of your argument? What kinds of “traces” of the Trinity might we see in in creation?

Leithart:

All I give in the book is a sample. I talk in the book about personal relationships resembling the relationship of the Triune Persons. I never can be in the same intimate communion with another person as the Father is with the Son, but my communion with other persons mirrors, dimly, the relationship of the Triune Persons. We can see this, for instance, in the way that one person leaves an imprint on another. I have certain habits and instincts that I picked up from my father; you can “see my father in me.” In some sense, thin perhaps, but real, he “dwells” in me. He lives in my memory; but he also lives in the way I use and hold my body, the inflections and pauses of my voice, the way I scold my kids.

The most obvious expression in personal relations is in sexual relations. When a man and woman make love, they are really, physically, “indwelling” each other, encircling each other. That’s one reason why the Bible speaks of God’s relationship with his people with marital, bridal analogies: He’s telling us that He is bringing us into His embrace, just as the Father, Son, and Spirit are in an eternal embrace.

I think it’s really important to remember that we have bodies as we think through these things. Sometimes we think about our relationship to the world as if we were disembodied souls. But our relationship with the world is through our bodies. And once we see that, we can see that our relationship with the world is somewhat “perichoretic.” I am “in” the world, but every moment little bits of the world come into me (oxygen, and at meal times food and drink). If the world were just “out there” and not also “in me,” I wouldn’t live very long. A living relationship between me and the world is a perichoretic relationship.

I see it in things like music and language too. In a dim, analogical sense, we can say that words “inhabit” words. Is it accidental, for instance, that the word “habit” is right there inside, literally inside, the word “inhabit”? Think what a good poet could do with that! We bring the world into our language when we name something; those itty-bitty things that are smaller than atoms always existed (presumably) but they never entered our language until someone discover them and called them “quarks.” And our language enters the world too – we make things happen by speaking.

Music is one of the best examples, but I’ll stop there because I want people to have to get the book. Trust me, though, the music stuff is the most important stuff in the book. But I’m not going to tell you about it in this interview. You’ll have to fork over some money to learn the secret. If your readers think they’re going to get something for nothing out of me, well, I wasn’t born yesterday.

Books At a Glance:

Just to be clear, you are not trying in your book to establish the doctrine of the Trinity via “natural theology,” right?

Leithart:

That’s right. I wrote the book to draw the reader in, starting with observation about the way the world is, what it’s like to be a person in relationships, what sex means, how language works. Eventually, I get to the point where I argue that everything shows this recurring pattern because it was created by the Triune God whose inner life is this pattern.

That’s the way the book is written, but that’s not how I arrived at my conclusions. I started with John 17 and other passages, and noticed that Jesus expects “perichoresis” to show up in the way we are connected to God and to one another. And then I started noticing a similar movement and whirling, swirling pattern in the world around me. I wouldn’t have noticed it, or noticed that it recurs in various guises, without starting from the Trinity.

Books At a Glance:

What precedents are there for this kind of “theological speculation,” as you call it, in the history of the church?

Leithart:

As I said, this has been part of the Christian tradition for a long time. The earliest and most elaborate example is Augustine’s de Trinitate, “on the Trinity.” There’s a lot of debate about what Augustine is up to in that treatise, but it’s obvious that he seems some kind of analogy between love and the Trinity, and between the human soul and the Trinity. He talks about the triadic nature of love: You need a lover, you need a beloved, and you need the love that unites them. Then he goes on and on with “psychological analogies” to the Trinity, suggesting that the soul’s capacities are also triadic – memory, intellect, and will. And he sees these as somewhat perchoretically intertwined – your memory doesn’t work without intellect and will, and so on. Richard of St Victor picks up on and develops the analogy of love during the Middle Ages, and there’s a good bit of speculation about created traces of the Trinity in English theology and poetry after the Reformation. Donne loved to play with Trinitarian themes, for instance.

What I don’t find in the tradition is the specific thesis that I’m developing – that there are perichoretic traces of the Trinity everywhere. The idea isn’t original with me by any means. You find it in recent theologians like Colin Gunton. But as far as I know it’s not played a significant role in Trinitarian speculation in previous centuries.