Reviewed by Ben Rogers

Introduction

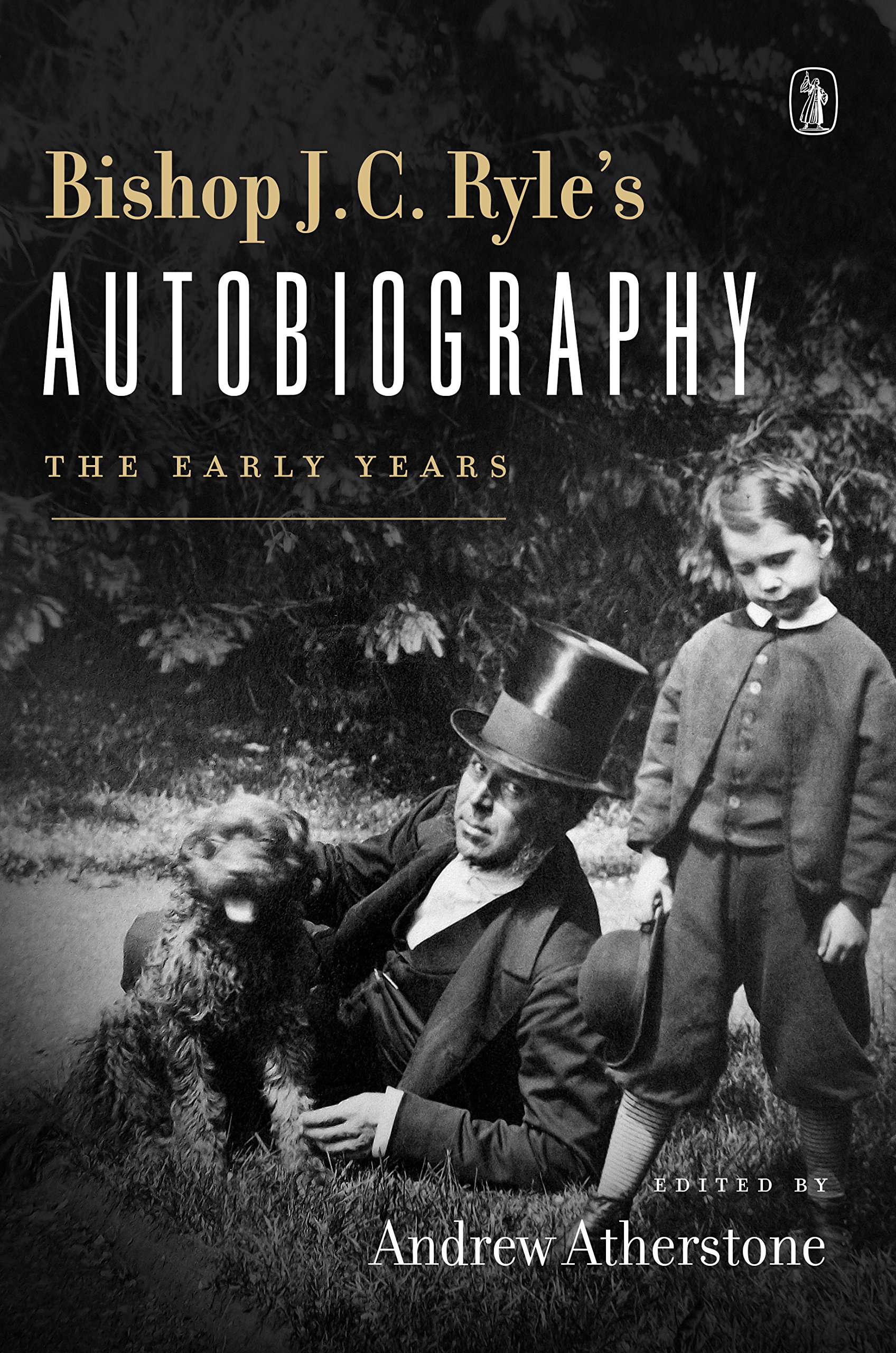

For the second time in recent months, the Banner of Truth has published another outstanding tribute to Bishop J. C. Ryle to commemorate his 200th birthday. The first, J. C. Ryle: Prepared to Stand Alone by Iain H. Murray, is an excellent biographical introduction to the famed Anglican bishop’s life and work. This volume, Bishop J. C. Ryle’s Autobiography: The Early Years edited by Andrew Atherstone, is, perhaps, even more outstanding.

For more than four decades, those wishing to read Ryle’s autobiography had to settle for Reiner Publication’s J. C. Ryle: A Self-Portrait (1975) edited by Peter Toon. The Toon edition is out of print, hard to find, and the copy of a copy of a copy. The new Banner of Truth Trust edition is based on Ryle’s original text, recently rediscovered in December of 2015 among the private family archives of John Charles Prince of Sayn-Wittgestein-Berleburg, grandson of Edward Hewish Ryle and named for his great-great grandfather, Bishop John Charles Ryle. In short, the new Banner edition of Ryle’s autobiography is now the definitive edition of this critically important primary source. Students of Ryle and his era more generally will be delighted – and this is only the first half of the book. The second half of the work consists of a nearly two-hundred page appendix, which contains a number of extremely rare and deeply interesting documents that shed light on Ryle’s “early years.”

The Autobiography

Ryle penned his autobiography, according to Atherstone’s estimation, in the early summer of 1873 at the age of 57. His account is rather short: the original copy was only 169 pages, which pales in comparison to the four-volume autobiography of his contemporary, Charles Spurgeon. The narrative ends rather abruptly with the death of his second wife and close of his ministry in Helmingham. In the years between the close of the autobiography and its composition Ryle became a national figure and the leader of the Evangelical party of the Church of England, and it is a pity that he left no record of his thoughts about these critical years of his life. And it is a personal text, not written for private consumption. It was originally written for his five children. Even with these shortcomings, this document sheds tremendous light on the personal thoughts and feeling of a notoriously private person.

Chapters 1-2 focus on Ryle’s family and childhood respectively. The former is largely genealogical in nature, and would be of little interest to most readers – apart from his father’s wealth, his grandfather’s connection to the revival leader, John Wesley, and his mother’s connection to the famous inventor, Sir Richard Arkwright – were it not for the editor’s footnotes, which help the patient reader appreciate Ryle’s family connections. The latter contains a brief record (5 pages) of “the statistical facts” of the first eight years of his life, which consists of a series of loosely-connected memories and impressions. The picture he paints of his home and childhood is one of wealth, comfort, and happiness, but a lack of real spiritual concern.

Chapters 3-5 describe Ryle’s school days at Rev. Jackson’s private school (ch. 3), Eton College (ch. 4), and Christ Church, Oxford (ch. 5). Each chapter is interesting in its own right and provides valuable insight into both the author and the institutions he attended. Ryle’s account of his time at Eton deserves special attention as it is the second longest of the entire work and recounts a time of great personal transformation. He entered Eton a shy, awkward young man; he left a confident and accomplished scholar-athlete. From there he matriculated to Christ Church where he captained the University XI (cricket) and won a number of academic honors, including a very brilliant first-class in Literae Humaniores, which remained a source of pride for the rest of his life.

Chapters 6-8 recount a series of sweeping changes that took place during a relatively short but critical period of Ryle’s life (1837 to 1841). In chapter 6 he gives an account of his conversion and his new religious convictions, as well as the opposition they engendered among his friend and family members. Oddly enough, the most well-known element of this story – the powerful and emphatic reading of Ephesian 2:8 – is not discussed in great detail, but Appendix 4 “Canon Christopher on Ryle’s Conversion” fills in the gaps wonderfully. In chapter 7 Ryle relates the “many and various” “facts of [his] life” from 1837 to 1841, which included the purchase of the elegant Henbury estate, his elevation to various positions of leadership in Cheshire, and his preparation for a career in politics. On a more personal level, these were difficult years. His new religious convictions estranged him from his family and relatives, and their objections to his new faith kept him from “works of active usefulness to the souls of others.” However, everything changed in June of 1841 when his father’s bankruptcy ruined the family and thrust Ryle out of Henbury Hall and Macclesfield politics and into the ministry of the Church of England.

Chapters 9-11 give an account of Ryle’s life and ministry beginning from 1841 to 1861 in Exbury (ch. 9), Winchester (ch. 10), and Helmingham (ch. 11). Each chapter contains a brief summary of his ministry in each town, which includes details about the makeup of his congregation, the challenges he faced, his ministerial workload, his expanding influence, and his own estimation of his success. They are also unusually personal and provide a rare glimpse into J. C. Ryle’s personal struggles. Chief among them was the difficult transition from riches to rags and the death of two wives: the first in 1846 and the second in 1860 after nearly a decade of ill health. Though the narrative ends abruptly, what Ryle lacked in style he made up for in substance. The last three chapters of the autobiography provide some of the best insight into J. C. Ryle, the minister and the man, that can be found in any of his works.

The Appendices

Appendix 1 contains three generations of Ryle family birth records taken from the Ryle Family Bible beginning with its first owner, John Ryle senior (1744-1808), J. C. Ryle’s grandfather. At first glance, these details may seem uninteresting to all but the most ardent Ryle enthusiasts, but, as the editor points out in his helpful introduction, there is more here than mere genealogical facts. The record of baptism sponsors is particularly illuminating. It reveals the identity of some of Ryle’s closest evangelical friends, as well as the paramount importance he attached to theological convictions, as opposed to family ties, in his choice of godparents.

Appendices 2-3 contain texts related to J. C. Ryle’s formative days at Eton. Appendix 2 contains the text of four relatively short speeches the young Ryle gave before the Eton [Debating] Society in November of 1833. They represent the earliest surviving examples of his public oratory. Though the topics are diverse, they are bound together by the question of moral leadership, and they manage to be both interesting and illuminating at the same time. Appendix 3 contains a brief article entitled “The late bishop of Liverpool as an Eton boy,” written by his favorite son, Herbert, shortly after his death in 1900. It contains new information not included in the autobiography, such as the account of J. C. Ryle’s two floggings by the infamous headmaster, Dr. Keate. There is also a short text giving the measurements of Ryle as an 18-year-old, whose impressive physic was often a source of comment, as well as the measurements of his favorite Lyme mastiff, Caesar.

Appendix 4, which has been alluded to earlier, is Canon Alfred Christopher’s account of Ryle’s conversion. This is a tremendous and needful addition given the fact that Ryle’s conversion has achieved something of a legendary status among evangelicals – a testimony to the power of the public reading of God’s word – and yet the most critical and dramatic details are left out of his autobiography. Based on the information provided in the Canon’s account along with other material, Atherstone is finally able to locate church (Carfax Church) and the date (June 25, 1837) that Ryle heard the memorable reading of Ephesians 2:8.

Appendix 5 contains the text of five of Ryle’s earliest tracts. He would go on to publish hundreds more during the course of his ministry. Millions of copies were sold, and many were translated into a dozen languages. They brought J. C. Ryle international fame, and many are still read today as chapters in popular works such as Old Paths, Holiness, Practical Religion, and The Upper Room. Fans of the later tracts will undoubtedly enjoy these earlier ones, and the editor is to be commended for publishing these extremely rare documents.

Appendix 6 is Ryle’s funeral tribute to Georgina Tollemache, which was later published as Be not Slothful, but Followers (1846). In his autobiography, Ryle said she “really delighted in my ministry,” and that she “was the brightest example of a Christian woman I ever saw.” The sermon is a fitting tribute and reveals the spiritual qualities he valued most. In addition to providing the full text of the sermon, the editor also adds footnotes to demonstrate the range of his biblical quotations and allusions, which amount to more than 150 in a single sermon!

At first glance, Appendix 7 – “Ryle’s Last Will and Testament” – seems somewhat out of place in a volume with the subtitle “The Early Years,” but it is included because of what it reveals about the provenance of the Ryle family heirlooms. There are also a number of surprises in the will, and the editor does an excellent job of pointing them out and explaining them.

Conclusion

I cannot commend the Banner’s new edition of the J. C. Ryle’s autobiography highly enough. It is far superior, both in form and content, to the old Toon edition. The rare and hard-to-find texts that make up the appendices are a treasure in themselves. And the editorial work by Andrew Atherstone is simply outstanding. His introductions are clear and informative. And the hard work he put in on the many footnotes – all 1061 of them – enrich both halves of the book immensely. Bishop J. C. Ryle’s Autobiography: The Early Years is a must-have for Ryle enthusiasts and students of Victorian evangelicalism more generally. It is Ryle’s life in Ryle’s words in a readable, informative, and well-edited format.

Ben Rogers