Reviewed by Trey Moss

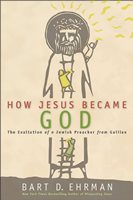

At face value How Jesus Became God looks promising. Bart Ehrman is a world-renowned scholar who has published and edited numerous academic works on textual criticism and early Christianity. Pastors or informed lay-persons would benefit from a thorough study like the book under review. Especially, since Ehrman seeks to present a full synthesis on Christology. Unfortunately Ehrman’s work on the historical identity and theology of Jesus, found in How Jesus Became God presents multiple problems.

As a historian Ehrman approaches the gargantuan task of producing a full work-up on how Jesus came to be viewed as God by the early church (p.2-3). However, he is not exempt from his own historical and philosophical presuppositions. What Ehrman proposes is a multifaceted and progressive understanding of Jesus’ divine identity through the NT canon into the early church fathers and church councils. “One of the driving questions throughout this study will always be what these Christians meant by saying ‘Jesus is God.’ As we will see, different Christians meant different things by it.” (p.3) Therefore, Jesus in Mark’s gospel can be a human being adopted by God in his baptism and thus made divine, or as in Luke’s gospel adopted as divine at his birth, or in Paul’s writings Jesus can be an angel who came down in human flesh and was later exalted to a greater divine status than he had before.

On this long strange trip Ehrman guides his readers through several different fields of study. These include: Greco-Roman mythology (ch.1), Second Temple Judaism (ch.2), the canonical Gospels and several apocryphal Gospels (ch.3-6), Pauline literature and theology (ch.7), the church fathers and early church councils (ch.8-9). All of which are necessary for gaining a proper understanding of early Christology, just not the brand Ehrman’s selling.

Ehrman begins his quest for how Jesus would become considered as divine within Greco-Roman mythology. “The place to start,” says Ehrman, “is with an understanding of how other humans came to be considered divine in the ancient world” (p.18). By starting here Ehrman wants his readers to understand that Jesus is not a complete anomaly in the ancient world. Greco-Roman mythology includes stories of Gods taking human form, humans becoming divine, and Gods procreating with human to produce semi-divine offspring (p.19-39). Rather than a great gulf between the divine and human realms, Ehrman commends his readers to see that the two realms are not as separate as one may think. There exists a divine pyramid structure: at the top is a supreme deity, while other, lower, divine beings exist somewhere in-between human and supreme deity.

Establishing the divine pyramid scheme of Greco-Roman mythology Ehrman turns towards Jewish theology. Here he sees a similar phenomena taking place. “Within Judaism we find divine beings who temporarily become human, semidivine beings who are born of the union of a divine being and a mortal, and humans who are, or who become, divine” (55). Ehrman paves over Jewish thought and literature with a Greco-Roman highway that leads to nowhere.

While there was indeed an explosion of interest of the strata of divine angels and demons, their names and obligations, it is simply wrong to say the literature of Second-Temple Judaism supports the worship of these divine beings as Ehrman does. “There were Jews whom we know about who thought it was altogether acceptable and right to worship other divine beings, such as great angels. Just as it is right to bow down before a great king in obeisance to him, they believe it is right to bow down before and even greater being, an angel, to do obeisance” (p.54). And again he says, “Ancient authors insisted that angels not be worshiped precisely because Angles were being worshiped” (p. 55). Ehrman gives no texts to support these quotes so it’s hard to know what authors to whom he refers. On other hand texts do exist which prohibit the worship of angels (Deut. 5:8; Tob.12:16-18; 3 En. 16:3-5;Col. 2:18; Rev. 19:10; 22:9).

A better understanding of Jewish thought and literature does not distinguish between divine and human, but creator and creation. Worship has not attributed to angels or other created heavenly beings because they were created. In this way are more like humanity than deity (cf. Rev. 19:10;22:9). Michael Bird’s “Of God, Angels, and Men” in How God Became Jesus (Zondervan, 2014) presents a clearer introduction to Jewish monotheism.

Ehrman’s treatment of Judaism helps us understand his particular approach to Pauline literature. Paul, in Ehrman’s framework, “understood Christ to be angel who became a human” (p. 252). Thus Paul’s Christology nicely fits with Ehrman’s framing of a diverse and progressive Christology (p.251-252). Ehrman uses only two Pauline texts to support his reading: Gal. 4:14 and Phil. 2:6-11. Ehrman does not mention other attempts to formulate Paul’s Christology or any other texts that would call his theory into question, thus leaving his readers to believe that Ehrman’s take by default right. Scholars like Richard Bauckham and Larry Hurtado, both of whom have published scholarly works on Ehrman’s present topic, are not properly reckoned with.

Furthermore the two texts Ehrman uses on his behalf do not necessarily support his conclusions. Galatians 4:14, for example, really has nothing to do with Jesus’ identity (p.253). In context, Paul is discussing how his gospel message was received “as angel of God, as Jesus Christ.” This does not provide interpreters of Paul with a lens for the rest of Paul’s Christology, as Ehrman would suggest (p.253). Rather gives Ehrman a proof text to skew every Paul wrote about Jesus. It is more likely that Paul is reflecting on an early Gospel tradition (cf. Matt. 10:40). The Galatians received the gospel of the sick and hurting Paul like as a divine messenger or as Jesus himself!

Next Ehrman calls Phil. 2:6-10 to his aide, yet it proves unwieldy to the Pauline Christology he seeks to construct. As Ehrman understands Paul, “… this poem presents an incarnational understanding of Christ – that he was a preexistent divine being, an angel of God, who came to earth out of humble obedience and whom God rewarded by exalting him to an even higher level of divinity as a result” (258). The comparisons between Jesus and God and Jesus and man do not fit Paul’s application if Jesus does not really meet both criteria of God and man. Additionally the Jesus-angel theory runs roughshod over the rest of Philippians, especially 3:3-12. Here Paul refers to Christ in relational categories only applicable to God, something also he does in his other letters (cf. Rom. 9:5; 1 Cor. 8:6,10; 1 Thess. 3:11-13). While both Jeremiah and Paul commend proper boasting is only in the Lord (Jer. 9:23,24; 1 Cor. 1:31; 2 Cor. 10:17), here Paul boasts in Jesus (3:3)! Ehrman’s imposed selective exegesis of Pauline literature harms his overall argument.

Finally, the narrative Ehrman presents is controlled by an imposed chronological progression that must exist for his thesis to work. Thus the identity of Jesus needed to progress from a human made divine, to an angel made human made divine again, to full blown God status. But as we have seen in part the literature Ehrman seeks to argue from proves something of the opposite. Rather than developing, Jesus’ identity was seen be one which shared a divine status with the creator Himself (cf. Deut. 6:5; Cor. 8:6)! Ehrman’s course of study is ultimately directed by his own philosophical presuppositions. He commits the one error he sought to avoid. “I am instead interested in the historical development that led to the affirmation that he is God. This historical development certainly transpired in one way or another, and what people personally believe about Christ, should not, in theory, affect the conclusions they draw historically.” (p.3) Nothing could be further from the truth.

What one believe does in fact determine the conclusions one draws. Interestingly enough, Ehrman takes a very post-modern approach to the canonical Scriptures and yet reserves himself from the same level of critique. Commenting on objectivity of historical reliability of the resurrection miracle Ehrman writes, “…any other scenario – no matter how unlikely, is more likely than the one in which a great miracle occurred, since the miracle defies all probability (or else it wouldn’t be called a miracle” (p.173). Thus Ehrman assumes that a general naturalistic outlook is above critique, and that miracles, no matter how well attested, must be ruled out. This is Humean logic, which assumes its own conclusion, and is not a compelling argument.

Ehrman’s attempt to provide a full-scale Christology is flawed. That does not mean it is not well written and enjoyable (and sometimes frustrating). Ehrman skillfully adds his own journey from evangelicalism to agnosticism within each chapter. Ultimately his thesis is not supported by the texts he uses for his arguments. It is the fear of the reviewer that Ehrman’s present work, written on a popular level, will be extremely influential. Pastors and teachers of the church need to work through works like Ehrman’s simply because they will be read by people in the pew. One positive aspect of Ehrman’s is his work with the literature of the New Testament world. Perhaps How Jesus Became God will prompt students and pastors to study the relevant texts of that period.

Trey Moss is an M.Div student at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and is currently an applicant for the NT Ph.D program.

Note: You may also like to see our interview with Michael Bird (ed.) on his response to Ehrman, How God Became Jesus.

You may also like to see our interview with Andreas Kostenberger and Michael Kruger on their The Heresy of Orthodoxy, Part 1 and Part 2.

And you may be interested to see our posts on Truth Matters and Truth in a Culture of Doubt by Darrell Bock, Andreas Kostenberger, and Josh Chatraw. See our blog and our interviews here, here, and here.