A Book Review from Books At a Glance

Reviewed by Michael Plato

Introduction

This is a book that is hard to place. The title, especially for Americans, does not help clarify the enigma. The subtitle does give a better picture: “The escalating challenges for Bible-believing Christians in Britain since the turn of the millennium.”

But what exactly is it? Part polemic, part history, part apologetic, part speculative fiction, part political pamphlet, it packs a lot into what is essentially a very brief read. The author, Julian Mann, is an evangelical Anglican vicar from the north of England. We are told in his bio that he used to be a journalist for the retail world and this appears to be his first book.

Synopsis

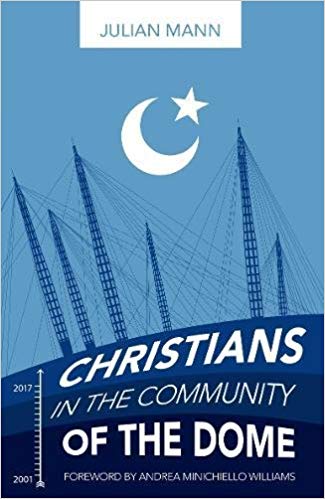

The dome of the title is the Millennium Dome, a kind of white elephant event center built on the shores of the Thames River in London to commemorate the year 2000. It acts as something of a symbol and starting point for Mann’s book. He sees the dome as a sleek, modern tower of Babel, and the turn of the millennium as the marker for a radical shift in British cultural life. He notes that shortly after 2001, “I began to sense that the attitude of the political class in our country was changing from a broad acceptance of Britain’s Christian heritage to hostile indifference” (11).

The bulk of the short book which follows is a dispassionate timeline of political and cultural events in Britain from 2001 until 2017. Some of these events are bland factoids, such as when elections were called and who became prime minister. Other events on the timeline, the majority in fact, have to do with events, legislation, court rulings and the like which impacted negatively on British Christians, or at least those with traditional or religious views. This segment, which goes on for forty pages, is meant to build in the reader a sense of the increasing and relentless hostility towards Christians and their values.

This hostility goes in two directions. One narrative strand to emerge is of the growing gay/transgender movement, especially towards gay marriage. The other narrative is of the growing strength and power of the Islamic community within Britain. The two movements, while diametrically opposed in their goals, both share a hostility to the traditional Christianity which has formed the basis of British society for a millennium and a half. What is also shown is that these two movements are being promoted and assisted by a vacillating ruling class which seems to be operating out of past shame and guilt and an optimistic fascination with novelty and self-recreation.

After taking the story up to the summer of 2017, with the Conservative Party’s mediocre re-election under Theresa May, the historical narrative ends. The book then jumps to the year 2050 and offers four speculative “histories” of that year, and what might befall Britain in the future. One narrative depicts a future where militant Islam dominates the country. Two other scenarios involve the repression of religion altogether, and a fourth—the hopeful one—depicts Christian revival in Britain.

Assessment

So what is to be made of this book? And more importantly, should you bother to read it?

I’ll admit to being somewhat doubtful when first picking it up. It’s opaqueness as to what it was up to did not encourage me. It seemed, with its disjointed mixture of fact and fiction, like an evangelical jump into postmodern literary experimentation. And it certainly does not offer much in terms of an in-depth explanation as to how Britain got to where it is now. But it nevertheless shows how major consequences are arrived at by a series of small but unrelenting steps.

It also gave me greater empathy for Christians in Britain and what they are going through (though the implications are also clear that we are largely on the same course here in North America, if only a few paces behind). Moreover, it shows the sadness of a great and magnificent culture which has so suddenly been diminished. And this has certainly been reflected elsewhere in the media in the past weeks and months. Britain may have begun to unmoor herself from its economic and political ties to the E.U., and it may be busily allowing a great deal of legislation through, but it ultimately seems to have no sense of what it wants to do, or where to go, or what it should stand for, because it has forgotten what it once was.

One can’t of course tie Christianity to the success or failure of one nation (though there does seem to be a remarkable correspondence between Christianity and national prosperity), and we cannot assume that any nation that identifies itself as Christian is actually “Christian” in terms of the faith of its citizens. Nevertheless, what is clear is that the community of the dome that has emerged in its place has proven itself to be a hollow structure.

Regardless of what kind of society emerges in the future of Britain, Mann points out that there will always be a need for faithful Christians to face trials of one kind or another. In this regard you may read this quirky, quick book as a warning as to what may come next, or a call to faithfulness in a brave new world.

Michael Plato is Assistant Professor of Intellectual History and Christian Thought at Colorado Christian University in Lakewood, Colorado.

Buy the books

CHRISTIANS IN THE COMMUNITY OF THE DOME, by Julian Mann