A Book Review from Books At a Glance

by Ryan M. McGraw

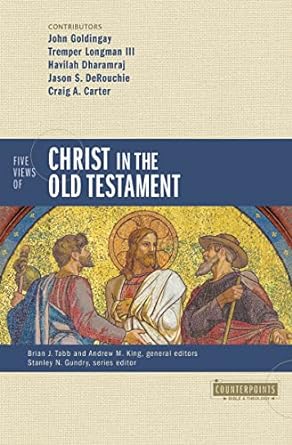

Christians, who have read the New Testament, know intuitively that the whole Bible is about Christ. Yet relating the Old and New Testaments and finding him throughout Scripture often raises difficult issues. Is every OT text directly about Christ? If so, then how? Are there overarching reading strategies we should pick up to see Christ better? Do the NT authors teach us how we should read the OT, or did they read Christ into texts in places where the Spirit could lead them, yet we dare not follow without divine inspiration? These are hermeneutical questions, meaning that the presuppositions we bring to interpreting the Bible, self-consciously or not, shape what we are able to see or not see in Scripture. The five authors in this volume represent five different approaches to seeing Christ in the OT. Placing them side-by-side has potential to promote deeper thinking about the relationship between Christ and the Old Testament. While not all the options presented are equally viable, readers seeking to be faithful to how Christ and the apostles read the OT will find much useful food for thought here.

The five views of seeing Christ in the OT in this volume are overlapping and compatible in many respects, while remaining disjunctive and incompatible at others. After presenting each view, the four other authors reply to it, followed by a rejoinder by the author, giving readers the feel of a moderated paper debate. All the authors take interpreting God’s Word properly seriously, placing the Trinity and Jesus Christ at the heart of biblical Christianity as well. The editors tasked each author with stating their principles and then applying them to Genesis 22, Proverbs 8, and Isaiah 42, resulting in an easy to follow pattern throughout the book. Additionally, the dialogical feature of the text results in a gripping paper-debate tone, leading readers to think deeply about the relevant texts and issues as they overhear the authors engage each other’s arguments. The remainder of this review outlines each author’s view, offering some critical engagement along the way, followed by a synthesis in which this review weaves together what is true from each approach.

John Goldingay (“the first testament view”) is the most radical author in the group. His approach hinges on his understanding of distinguishing between the meaning of texts in original context, and their significance for modern readers (22). Asserting his Trinitarian faith, he nonetheless argues that we should read the NT in light of the OT and not vice versa (21), which is what makes it a “first testament” view. While Jesus is the climax of the biblical storyline (28-29), Jesus is not, strictly speaking, in the first testament (38). He goes so far as arguing that we cannot prove that Jesus is the Messiah from the OT, which he later retracts to some extent (69). Perhaps most shocking is his assertion that OT features like temple, priesthood, and sacrifices “are simply realities” rather than shadows of NT realities; we can only see them as foreshadowing Christ in hindsight (70). Jason DeRouchie does not miss the irony in his reply to Goldingay that Colossians 2:16-17 overtly calls such features of the OT shadows pointing to Christ as their true substance (61). Still more radically, Goldingay presents, putting it generously, an ambiguous position on the authority of all written Scripture (102-104), making it appear that he is working from a different paradigm than the other authors in this volume. In the end, Goldingay’s “first testament” position is the least satisfying of the five. While he rightly directs readers to study the OT in its own context on its own terms, he does not adequately reflect the claims of Christ and the apostles to ways in which Christ is in fact in the OT.

Tremper Longman’s “Christotelic view” is, by his own admission, not fundamentally different from Goldingay’s “first testament view” (46-47). Both authors share the concern to read OT authors in their original contexts, searching for authorial intent on some level (80-82). Longman moderates authorial intent, however, noting rightly that we only have access to the meaning of the texts they produced, excluding their intent and understanding (81). “Christotelic” means that Christ is the goal of all Scripture, which results in a kind of double-reading of OT texts: once in their own contexts, and again in light of NT fulfillment and realities (86-88). We must not read the ideas of NT authors into the OT, but we must see Christ as the goal or telos of the OT texts as well. For this reason, there is often reason to depart from early church understandings of the OT, though “Biblical interpretation is an art, not a science” (87). Regarding the first reading, “What is important is to always read the Old Testament first – without appeal to Christ – to listen to its discrete voice” (87). Rather than seeing a seamless connection between the intent of the original author of an OT text and its NT fulfillment, however, he posits a kind of sensus plenior approach, in which the meaning of the original author may or not may not have been in harmony with those adopted by Christ and the apostles. Clarifying what he means, he notes that “[G. K.] Beale’s appeal to the cognitive peripheral vision of the Old Testament author is as desperate as it sounds. Explanations often given for how the Old Testament author could have understood the New Testament use are strained to the extreme” (85). Like Goldingay’s chapter, the upshot of Longman’s material is learning to study the OT on its own terms, while taking the forward step that God designed the whole Bible to culminate in Christ. The downside is that Longman undercuts divine intentions regarding Christ in various parts of Scripture as the story marches onward towards is Christological climax. What God means through distinct passages in light of the whole Bible is more important for Christians than what its human authors meant, though we should not divorce the two.

The third approach by Havilah Dharamraj (“reception-centered inter textual view”) reads as the most overtly post-modern viewpoint in this book. Production centered inter-textuality, represented later by Jason DeRouchie, emphasizes harmonizing the communicated intent of the human authors of Scripture with the overarching intent of the divine author, allowing for partial understandings of the same meaning and intent of the divine author by the human authors at the time to greater or lesser degrees (128). By contrast, reception-centered inter-textuality “resists speculating about how one text may be dependent on another (128-129), focusing instead of pairing a primary text with a second one (suggested to the reader’s mind by general familiarity with the Bible), and finally synthesizing the two into a “third text,” which is actually the reader’s response to reading the first two (129). As virtually all the other authors indicate in their replies, the danger here is making arbitrary decisions respecting which texts should go together as well as what readers should do with both. Despite such potential arbitrariness, aspects of her connections between Abraham offering Isaac (Gen. 22) and Christ’s humiliation and exaltation in Philippians 2 (134), as well as the line she draws between Proverbs 8:22-31 and Paul’s depiction of Christ in Colossians 1 (140) are breathtaking. Although this inter-textual approach fails to deliver an objective way of seeing Christ in the Old Testament, her chapter illustrates powerful ways in which Christology should shape how readers think, both theologically and devotionally, as they read their Bibles. Her method in the end will likely be more useful to preachers seeking to preach Christ as they expound and apply texts than it will be to general readers looking for a model for grasping how Christ and the apostles actually used the OT.

This reviewer sympathizes most with Jason DeRouchie’s “redemptive-historical” reading of Christ in the OT. Pivotally, DeRouchie opens with the divinely inspired nature of Scripture itself, which is prerequisite to his argument that the intent of the human authors converges with and is subsumed under the broader unified intent of the divine author (181-182). His actual interpretative steps in seeing Christ in the OT follow what he calls the “close context,” the “continuing context,” and the “complete context” (187). These categories drive readers to consider carefully the original context of texts, typological patterns relating them to early parts of divine revelation, and ways in which later revelation builds on both. These rules, in turn, yield seven possible ways in which Christ might be in OT Scripture, which I will not list here (188-191). The only liability to this viewpoint, if there is one, is risking importing too much into what OT authors understood regarding Christ at their particular stage of redemptive history. Yet if we make divine authorship and divine intent primary in reading the Bible as a whole, this liability becomes relatively small, since we are looking for natural ways of seeing the interdependence of biblical passages, focused on Christ, in light of a God-originated and Christ-directed message by design.

The final position, by Craig Carter, presses home a “pre-modern” approach to exegesis. As with his longer provocative monograph on the topic, Carter pursues his theme with characteristic catch-phrases like “Christian Platonism” and bordering over-the-top rhetoric. This is so much the case that Carter often becomes the primary target in the debates with other authors in the preceding chapters. Carter’s aim is to make divine authorship and intent primary in biblical interpretation, resisting post-Enlightenment trends towards making the intent of the human authors of Scripture our main focal point. Yet his concern over divine intent is so close to DeRouchie’s method that Carter could write, “I agree with nearly everything that DeRouchie has written in this chapter,” even calling it “the mirror image of my chapter” (228). The only difference he sees ultimately lies in his proffering a more overt metaphysical foundation regarding why theologians have been justified in interpreting the Bible in the ways that they have. Ostensibly, he believes that the “grammatical-historical” method is merely an attempt by conservative biblical theologians to moderate the essentially atheistic “grammatical-critical” method of liberal scholars (241). His contention is that without reviving pre-modern views of divine action through biblical texts, including the exegetical methods undergirding their Trinitarian and Christological stances, we will lose the Trinity, Christ, and the Bible themselves (242). Hermeneutics, in his estimation, is not so much a “method” as a “spiritual discipline” seeking sanctification (242), striving after “the divine author’s intended meaning as communicated through the human author’s words” (243). Interpretation is thus more of an art than a science, rooted in “a theology of hermeneutics” (249-251). For such reasons, Carter does not give readers steps for seeing Christ in the OT, but instead highlights the principles of the unity of Scripture, the priority of the literal sense, the reality of the spiritual sense, and letting Christology control the meaning of texts (251-256). While his emphases on spiritual reading, submission to divine authority under divine action through texts, and his zeal for Trinitarian and Christological aims in Scripture are spot on, his approach leaves readers with a sense of intangibility as they seek to understand the Bible on its own terms. Though he notes more clearly in this book than he does in his monograph that the “Great Tradition” is not monolithic, his dogged appeal to the unmodified medieval fourfold sense of Scripture (quadriga) is somewhat puzzling, since he does not ultimately adopt medieval uses of this method (292). Readers might walk away with an energizing (and much needed) zeal for reading the Bible to hear from, know, and worship the Triune God, without really knowing how to understand the parts of the Bible better than they did before.

Sifting through the insights of each author in this book, is there a path forward for seeing Christ in the OT? Taking each view in order takes the following shape.

- First, we should respect what each biblical author meant in each of their own contexts.

- Second, we should retain the big-picture trajectory of Scripture, culminating in Christ.

- Third, recognizing the unity of Scripture in Christ, he should always be in our hearts and minds experimentally, every page reminding us of him and leading us to worship him and preach him.

- Fourth, we should see objective inter-textual connections produced by the divine author through the human authors of the Bible.

- Fifth, theological convictions about the Trinity and Jesus Christ should drive how we read the entire Bible.

Taken together, such reading strategies can help us listen to Scripture carefully, reading Christ on its pages without reading too much into its pages, while always reading (and preaching) devotionally and doxologically whether Christ is directly in a passage or not. In the end, seeing Christ in the OT is a spiritual discipline resting on divine action through Spirit inspired texts. As noted above, hermeneutics is more of an art than a science. Yet as Augustine taught the church long ago, even if we make mistakes along the way, if the Triune God is the thing we are always prayerfully searching the Scriptures for, loving and enjoying him along the way, then we are not far wrong and our mistakes are never fatal.

Ryan McGraw

Greenville Presbyterian Theological Seminary