A Book Review from Books At a Glance

By Ryan Speck

Context

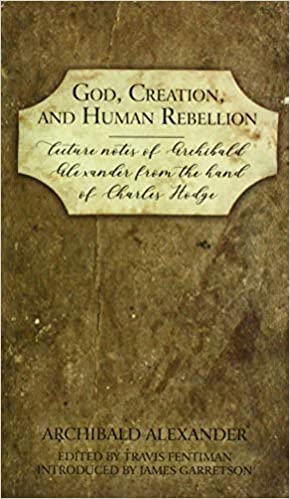

Stumbling upon cursive notes in an online library, Travis Fentiman realized the treasure he discovered—Charles Hodge’s handwritten notes from Archibald Alexander’s seminary classes! He assembled a ten-person team to transcribe this work, which is now a 169-page book available from Reformation Heritage Books.

Editor

Travis Fentiman is a graduate of my alma mater, Greenville Presbyterian Theological Seminary, and is described as a Probationer of the Free Church of Scotland (Continuing).

Author (of the Introduction)

Dr. James M. Garretson wrote a lengthy, 25-page Introduction. Dr. James M. Garretson is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church in America. He is the author of Princeton and Preaching: Archibald Alexander and the Christian Ministry, has edited Princeton and the Work of the Christian Ministry, and selected and introduced Pastor-Teachers of Old Princeton.

In the Introduction to this book, Garretson explains the historical period and the importance of the transcribed notes from Hodge. Why should anyone be interested in some student’s notes from an ancient seminary class? These are “the classroom records of two of the greatest theologians and seminary educators in the history of American Christianity” (xv). That is, “the lives and literary legacies of Archibald Alexander (1772-1851) and his prize student and successor, Charles Hodge (1797-1878), are without peer in the record of American theological education” (xv).

Garretson details, accordingly, the life and teaching of Alexander, making sure to inform us that Alexander was a father figure to the younger Hodge, who lost his father at an early age. Ever the bright student, Hodge—destined to join Alexander on the faculty of Princeton—sat at the feet of this learned and zealous father-figure, recording notes that have been recovered for posterity. The “compact format” of these notes “allows a quick summary of key matters brief enough to be easily digested but substantive enough to provoke additional thought and inquiry” (xxxix). In short, “today’s reader is able once again to join Hodge and other young men in the lecture hall as their revered professor explains the manner in which the ‘deposit of truth’ finds expression in systematic doctrinal formulation” (xxxix).

Contents

Hodge organizes his notes throughout the book by use of catechetical instruction. That is, he includes five hundred questions with their answers. These five hundred questions are further divided by subject into seventeen chapters:

- Philosophy of the Mind

- Theology

- Revealed Theology and Prophecy

- Inspiration

- Attributes

- Trinity

- Decrees

- Predestination

- Election

- Reprobation

- Creation

- Providence

- Angels

- The Covenant of Nature or of Works

- Seals of the Covenant

- Sin

- On the Will

Evaluation

Reading someone’s class notes is like hearing one side of a phone conversation already in midstream. As you read these notes, therefore, you have the sense that you are missing a great deal. While the content available to you may be thought-provoking and useful, you certainly don’t have everything! At times, as you read this book and put yourself into the classroom setting, you want to raise your hand and ask a question of clarification, but you can’t. There is, consequently, a sense of frustration at times when reading these notes.

Accordingly, I had the lingering question of whether Hodge captured Alexander’s ideas well, or whether he neglected to write down crucial information. After all, Hodge was not preparing these notes for publication. Perhaps Hodge understood many things already so that he only recorded the facts he needed to remember? For example, when Hodge wrote that by the Fall “Adam lost the image of his Creator” (p. 131), what exactly did he mean? Did Alexander teach his class that holiness is the image of God (e.g., p. 121), which holiness was lost by the Fall? Or, did he mean that something more than man’s holiness was destroyed by the Fall? It is difficult to pinpoint Alexander’s teaching on such matters by reading this book of class notes alone.

Further, the lack of Biblical references and exposition of Scripture was surprising. For example, you must read until the 20th page before you arrive at the first, explicit Scripture reference. This means, there is a total of one Scripture reference in the first two chapters! Likewise, in the final chapter of this book (pp. 137-153), you will not find a single Scriptural reference. Throughout the book, Hodge does include many Scriptural references. Yet, at times, you feel as if you are reading a philosophical work, not an exegetical one.

In addition, these notes lack any significant application of the doctrines that Alexander taught. Why do these doctrines matter? What should be our response? How do they mold us and shape us into the image of Christ? How should our character be formed by these glorious truths? Practical applications of any sort are few and far between (e.g., pp. 85, 108-109). Again, did Alexander provide scant pastoral applications, or did Hodge simply absorb them in class, without recording them in his notes? In any case, the professors at the seminary I attended, seeking to prepare pastors for the ministry, were intent upon including clear, practical application throughout their classes—from which I personally have benefitted greatly, which is why I was surprised not to see such application in Hodge’s notes.

However, taking these notes as they are, you certainly gain a sense of the depths of thought in the seminary classes of that day. You gain a sense of how deeply the men of that day delved into philosophical reasoning, parsing out and thinking through doctrines. You also gain valuable summaries of doctrines—outlined and bullet-pointed. For example, on pp. 56-57, you find a concise summary of the Trinity as revealed in the OT (complete with Scripture references) and a four-point summary of why the Trinity is a fundamental doctrine of the Christian faith.

When you read this book, expect to read it slowly, pausing frequently to roll the ideas over in your mind. Perhaps, you should plan to read a bit of it each day, slowly digesting each part. Better yet, plan to read a bit of it each day and gather with fellow believers interested in thought-provoking discussions in order to digest it and think through the doctrines together. Or you might purchase it for a reference volume. What did Alexander teach on the subject of angels? Turn to pp. 111-120 for 33 questions and answers to provoke your thought on this subject.

Certainly, this historic book brings you into the classroom of great theologians. Clearly, you can benefit from it. However, since it is a collection of classroom notes—not intended for publication—you will face challenges in understanding and learning from it.

Ryan Speck

Review Editor for Theology, Books At a Glance