A Book Review from Books At a Glance

by Ryan Speck

Introduction

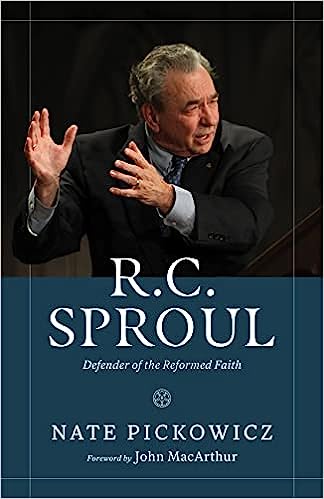

Without a doubt, R.C. Sproul stands as one of the greatest figures in Christianity today. His “giftedness as a teacher of theology is unsurpassed by anyone in our generation” (p. i). “R.C. Sproul could make the most majestic, complex, or sublime doctrinal themes accessible to any listener without dumbing down the content or sacrificing the grandeur of the subject” (p. ii). He “was Martin Luther without the insanity” (p. 1). “He had a John Calvin mind with a Billy Graham reach” (p. 125). Certainly, his life is worth contemplating for the enrichment of our own.

In this biography, Nate Pickowicz focuses upon Sproul’s battles for the truth, suggesting “loosely” that each of Sproul’s five decades of ministry correspond to battles for each of the five Solas of the Reformation (p. 2). “While he never went looking for a fight, the fight always seemed to come to him, and he never backed down” (p. 3).

Pickowicz writes in a factual, objective manner. He does not evaluate or critique but simply reports. He clearly admires Sproul but is simply interested in laying out the facts for the reader’s consideration and profit. Further, Pickowicz self-consciously recognizes the danger of hagiography and intends to avoid it, writing: “All too often we place our heroes on pedestals, exalting them higher than they ought to be. . . . respect and admiration are fitting for us insofar as we give glory to God for blessing His people with good teachers” (pp. 1-2).

Formative Life (Chapters 1-2)

In the opening two chapters, Pickowicz traces the life of Sproul from his forefathers to his education leading to ministry. These chapters are filled with interesting details about Sproul’s life. However, if you have read Sproul widely, you will likely know all these details already. For, Pickowicz draws exclusively from Sproul’s own writings to provide these details—every footnote in this section cites only writings from R.C. Sproul.

Yet, these details of Sproul’s personal life are necessary to explain his zeal to defend the faith. For example, when Sproul experienced conversion to Christ, he was shocked to be met with anger and rejection from his own family, friends, and even his childhood minister. The minister responded, “If you believe in the resurrection of Christ, you’re a damn fool” (p. 15). Likewise, at school, professors abused and scorned him for his religious beliefs: “That’s the most narrow-minded, bigoted, and arrogant statement I have ever heard. You must be a supreme egotist to believe that your way of religion is the only way” (p. 22). Even at seminary, “The vast majority of the incoming faculty from Western brought with them a blend of theological liberalism and neo-orthodoxy . . .” (p. 24). Thus, when Sproul preached his senior sermon on sin, “the dean of the seminary stopped him in his tracks filled with rage. He began to yell in front of the crowd, physically pushing R.C. back up against the wall, and said, ‘You have distorted every truth of Protestantism in that sermon this morning!’” (p. 27). Clearly, Sproul’s experiences during his earlier years prepared him to fight against the liberalism that had pained him so personally.

Theological Battles (Chapters 3-7)

The five theological battles detailed in these chapters are (in my words): inerrancy (sola Scriptura), sovereignty (sola gratia), justification (sola fide), worship (solus Christus), final days (soli Deo gloria).

Sola Scriptura

As Sproul was becoming well-known in the ’70s, beginning a L’Abri-like ministry called Ligonier Valley Study Center as well as publishing Tabletalk and recording audio and video lectures for distribution, the Kenyon case involving the inerrancy of Scripture raged in the UPCUSA. In response, Sproul left for the PCA, arranged a Ligonier Conference on the Inspiration and Authority of Scripture, and wrote “The Ligonier Statement,” which each conference speaker signed. Further, Sproul became “the point man” for the International Council on Biblical Inerrancy and was among those who signed The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy. Sproul believed, “If you take away the Word, you take away my life. I have nothing left because this is the Word of Christ. If you take away the Word, you take Him away” (pp. 47-48). During this battle, Sproul forged deep friendships with like-minded co-laborers.

Sola Gratia

In the ’80s, Sproul “would make his mark teaching the Christian world about the nature of God” (p. 55), including the imago dei, defending the truth about God through apologetics, and, after his “second conversion,” defending the holiness of God, especially seen in the doctrine of predestination. However, his ever-increasing audience took offense at his teaching of predestination.

Sola Fide

The ’90s contained Sproul’s most difficult battles. After surviving “the deadliest train crash in Amrtrak history” (p. 73), he was shocked and grieved to discover that some of his closest allies in the faith had signed a compromising doctrine called Evangelicals and Catholics Together (ECT): “in my career as a teacher of theology and in my life as a Christian, I cannot think of anything that has come remotely close to distressing to the depths of my soul as much as this document has distressed me” (p. 83). Sproul was not quarrelsome by nature but winsome and kind-hearted: “It was not uncommon for R.C. to finish a message only to turn to Vesta [his wife] afterward and ask, ‘Was I kind enough?’” (p. 77). However, when salvation was at stake, Sproul showed extraordinary zeal. During a meeting with friends who had signed ECT, “R.C. became so impassioned that he climbed up on the table and pointed his finger at one of his friends, and said, ‘I don’t think you get it. This is about whether you’re saved or not” (p. 83). During this decade also, Sproul’s mentor, Gerstner, died.

Solus Christus

At the end of the ’90s and into the 21st Century, Sproul felt that something was missing in his life. “I realized then that every one of my heroes from church history, theologians such as Augustine, Calvin, Luther, and Edwards, preached from a pulpit before his own congregation in addition to his daily teaching of theology” (p. 92). St. Andrew’s Chapel began, with Sproul as lead preacher. This allowed him opportunity to preach through books of the Bible, focusing upon the deity of Christ especially, and to worship Christ with reverence.

Soli Deo Gloria

During the last decade of his life, Sproul published many books, launched Reformation Bible College, began praying for global revival and established teaching fellows at Ligonier (anticipating a time of transition). When asked about Heaven, Sproul answered that everything else could wait, except “the sheer joy of being in the presence of God and enjoying the beatific vision—of seeing Christ face-to-face. I don’t know if that would ever wear off. I’d be satisfied to do that, I think, for eternity” (p. 123).

Conclusion

Pickowicz does not critique but presents. No doubt, he believes that this is his job as biographer, and I would, generally, agree and commend him for this work. However, to really learn from a man’s life, you must evaluate what is commendable to emulate and what is lamentable to avoid. That work is left to the reader.

Further, while packed with interesting and valuable information, this book also had some gaps and would have benefitted from more development. For example, when summarizing the opposition Sproul faced to his conversion, Pickowicz mentions Sproul’s sister (p. 18). However, that is the first and last time he mentioned her. How did she oppose his conversion? We are left hanging. Likewise, it is unclear how each chapter especially focuses upon Sproul as Defender of the Faith. How exactly is becoming a pastor of a local church specifically related to defending the faith, for example (pp. 91ff.)? Defending it against whom exactly—the congregation? And, how does becoming a pastor of a local church point us especially to solus Christus (as opposed to, for example, sola Scriptura)? Pickowicz’s use of the Reformation Solas seems forced—at least, not well-developed. Although the information was always useful, I was left wondering, at times, how it advanced his theme and fit with his outline.

Certainly, I learned much from this book, gleaning many helpful quotes and illustrations for sermons, which I have already tested in conversations to good effect! In my estimation, by reading this book, you will learn about the man, Sproul, grow in appreciating his prodigious work and sincere character of faith, and you will praise God for His gracious work in men, humbly pleading with God to work so in you also.

Ryan Speck