Review by Andrew Ballitch

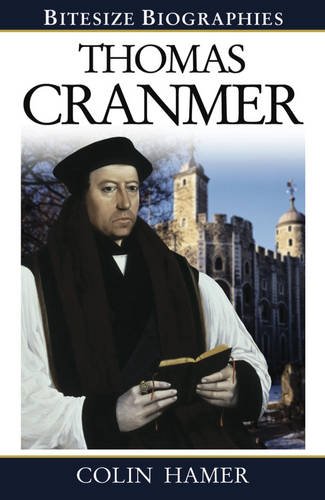

Thomas Cranmer’s influence on the English Reformation was unequaled. As the architect of the Church of England, he facilitated the split with Rome and later authored the Book of Common Prayer and what would become the 39 Articles. Remarkably, however, relatively little has been written on Cranmer compared to Reformers such as Luther, Zwingli, and Calvin. In this volume, Colin Hamer seeks to present an accessible survey of Cranmer’s life, arguing that “despite his faults, [Cranmer] lived true to his understanding of Scripture during a difficult time. Furthermore, his heart, mind and life were directed towards the furtherance of the gospel” (118).

The author picks up with Cranmer’s birth in 1489 and narrates the events of his life to his martyrdom in 1556, a complex story of development, compromise, and progress. Cranmer’s story is very much intertwined with the middle three Tudor monarchs: Henry VIII, Edward VI, and Mary I. Henry made Cranmer Archbishop of Canterbury, the highest ecclesiastical position in England, in 1533, the same year he separated his realm from the Roman Catholic communion. While Cranmer experienced gains and losses in his reform project and was largely held back by the conservative Henry, Hamer helpfully points out that Cranmer remained close to Henry and maintained his support for the rest of the king’s reign, something which no other relationship could claim. With the ascendancy of Edward, Henry’s only male heir, who was young and thoroughly Protestant, Cranmer was empowered to accelerate the English Reformation. The significant progress was halted with the early death of Edward and the transfer of rule to Mary, Henry’s oldest daughter and a devout Roman Catholic. After several years of prison and a wavering between recantations and bursts of courage, Cranmer met his fate. Burned alive as a heretic, Cranmer in the end provided a bold witness for his long-held evangelical convictions.

Hamer had the difficult task of writing a short biography of hugely important figure, whose development took place in an amazingly complex historical situation. The effort is an overall success, though there are a few particularly helpful points readers should notice. One is his explanation of Henry’s famed divorce of Catherine of Aragon, the divorce that eventuated in the split from Rome. While discussions often emphasize the politics and motivations in the situation, the biblical consideration is often lost. All else aside, there was a real wrestling with actual texts, such as Leviticus 18:16 and 20:21, as well as Deuteronomy 25:5, and Hamer walks us through their interpretation. Hamer’s evaluations of key personalities are another strength. He of course gives his estimation of Cranmer, devoting his concluding chapter to this assessment, but he provides further appraisals as well. One example will suffice: Thomas Cromwell. One of Henry’s most able advisers, he lost favor with the king and therefore his head. Hamer explains that Cromwell was the political genius enacting Cranmer’s desired reforms, though Cromwell seems to have backed such changes so far as they enhanced his power and wealth. He also ruthlessly dispensed with those who got in his way. While Cromwell had a close working relationship and even friendship with Cranmer, there is little evidence that shared the Archbishop’s personal faith in the gospel.

While Hamer is indeed largely successful in his challenging task, there are a few areas that could be improved. The first is cosmetic in nature. At times his narrative is a bit like sound bites. The material in individual chapters can feel like unconnected snapshots with anecdotes interspersed and occasionally unexplained. While the chronological flow and chapter divisions work nicely, chapters by themselves sometimes lack coherence. A second issue is Hamer’s evaluation of Cranmer’s evangelicalism. After cataloging Cranmer’s theological viewpoints on key issues, Hamer concludes that “by the end of his life [Cranmer] had arrived at evangelical convictions which meant that he would not be out of place in a twenty-first-century evangelical church,” with the exceptions of his views on Church and state and related belief in temporal punishment of heretics (108). This evaluation needs to be pressed further. It is precisely this carry-over from Roman Catholicism—the wedding of Church and state, coupled with infant Baptism—that produces an internal tension, even contradiction, when the evangelical doctrine of personal faith is added to it. The main streams of the Protestant Reformation did not begin to resolve this inconsistency until the seventeenth century. I am not confident that Cranmer, or Luther or Calvin for that matter, would be comfortable in twenty-first-century evangelical churches. That said, Hamer’s overall assessment of Cranmer, overwhelmingly positive while recognizing human failures, is on point.

As the author notes, the magisterial account of his subject is Diarmaid MacCulloch’s Thomas Cranmer (1996), a massive volume requiring a certain resolve and probably the requirement implicit in being a historian of the period to wade through. What Hamer offers is accessible and enjoyable to read. A great first introduction to Cranmer and his English Reformation. I recommend it.

Andrew Ballitch is a pastor at Hunsinger Lane Baptist Church in Louisville, Kentucky. He holds a PhD in church history and historical theology from Southern Baptist Theological Seminary.