A Book Review from Books At a Glance

By Thomas J. Nettles

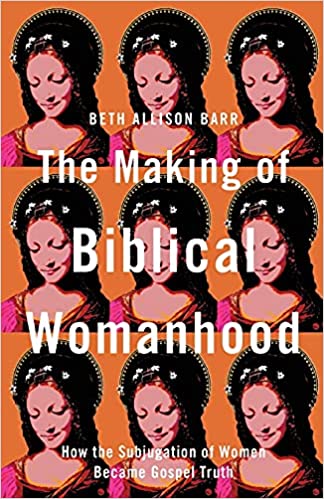

Beth Allison Barr teaches at Baylor University where she serves also as associate dean of the graduate school. She has been president of the Conference on Faith and History. Her presidential address for 2018, published in Winter edition 2029 in Fides et Historia, serves as a seedbed for the views she expresses in this book. The subtitle of the book is an excellent summary of its content. She depicts complementarianism as a subjugation—conquering, taking dominion over, making subservient—of women; she follows a line of development through history that brought about this subjugation; and this subjugation now is seen, although it has not always been so, as consistent with and an expression of the gospel (cf. 41). She has a long list of evangelicals—preacher/pastors, professors, denominational executives, writing theologians, conference leaders—who led the charge in this pedagogy of domination “transforming a literal reading of Paul’s verses about women into immutable truth” (189).

In her address to the Fides et Historia society, she isolated the “fundamentalist obsession with inerrancy” as the contemporary doctrinal phenomenon that “cast feminism in direct conflict with the word of God especially in the Pauline texts for women to be silent and submissive.” In this address as well as in this book she presents this “obsession” with inerrancy and these specific Pauline texts (Ephesians 5:22, Colossians 3:18, 1 Timothy 2:11-15, 1 Corinthians 11:3, 1 Corinthians 14:34) as having gained traction around 1940. She combines inerrancy and the Pauline emphasis as a deadly combination that became “the ultimate justification for patriarchy.” (190) Fundamentalists contended with oppressive success, Barr observes, that should one doubt inerrancy and be skeptical about a “plain and literal interpretation of Pauline texts about women,” they would “hurl Christians off the cliff of biblical orthodoxy” (190).

She gives her own treatment of several of these Pauline texts on pages 43-70 and intersperses her treatment with summary phrases. Citing John Paul II, she suggests that “using Paul’s writings in Ephesians 5 to justify male headship and female subordination in marriage would be the equivalent of using those passages to justify slavery” (45). “Instead of endowing authority to a man who speaks and acts for those within his household, the Christian household codes offer each member of the shared community—knit together by their faith in Christ—the right to hear and act for themselves” (49).

This impressionistic reworking of the meaning of the text would render an unusual combination of instructions. Does this mean that Christ has set children free to disregard the instructions of their parents and “act for themselves?” She accepts the “mutual submission” argument from certain commentators on Ephesians 5:21, criticizes the ESV in its contextual location of the verse as a summary of what should guide the instruction in verses 15-21 in distinguishing themselves from pagan culture. The translators followed the suggested arrangement of the United Bible Society text of 1966 as well as how naturally in context the participle follows from the previous admonitions. Instead, plausibly, she treats it as an imperatival independent participle introducing the household code of 5:22-6:11. That placement, somehow is seen as transforming the “plain and literal sense” of all the instructions that follow, virtually neutering the verbs of instruction.

Does that relocation of verse 21 mean that the participial force rendering the translation “submit to your own husbands,” and “wives should submit in everything to their husbands” even “as the church submits to Christ” mean really that wives have no admonition to live in submission to their husbands; can we thus imply that the church has no obligation to live in submission to Christ? Does it do the same to the admonition to husbands, in the form of a clearly stated imperative, to love their wives as Christ loved the church so that “mutual submission” in this context alters the force of that command? Are children now, because of the transforming nature of the gospel in producing mutual submission free to disregard, “Children, obey your parents in the Lord, for this is right,” or, commensurately, have no further moral duty to “honor your father and mother?” Paul was just kidding and really had no serious moral idea in mind governing existing relations when he wrote, “Slaves, obey your earthly masters with fear and trembling, with a sincere heart, as you would Christ, not by way of eyeservice, as people-pleasers, but as servants of Christ.” Even so, the duty of the master is relativized if not utterly neutered when told.

In light of the general mutuality of the condition “knowing that whatever good anyone does, this he will receive back from the Lord, whether he is slave or free,” that they should “do the same to them.” Masters should, in fact, act in relation to them as a servant of Christ, with good will, expecting that the relationship is governed not by them but by God. In this light, Paul commands, “stop your threatening” knowing that the ultimate master of both is the Lord in heaven, who will judge all these relationships without partiality. The Lordship of Christ over all does not diminish the relative duties owed in each of these relationships.

Why has Paul gone into such detail about the duties fitting in these various relationships if in the end they are rendered plastic by their connection with verse 21? Paul should have said “Wives submit to your husbands” and also “Husbands submit to your wives.” He should have written, “Children, obey your parents and bring them up in the discipline and instruction of the Lord,” and “Parents, obey your children.” He should have commanded, “Masters, obey your earthly slaves with a sincere heart as you would Christ.” But he did not: he explained in detail, even given the connection of 21 with 22 rather than a summary of 15-20, how God expects the relations of persons and various states in the church to relate to one another.

Barr, assuming the implication of how the verses connect, invents a new text. She concludes that in the complementarian version “the call for husbands to submit,” impliedly to their wives, “is minimized—not because Paul meant it that way but because the complementarian translators of the ESV wanted it that way” (50, 51). Nowhere in the critical text have I seen even a “D” reading for a text probably lost somewhere in manuscript transmission that calls to the husbands. The lively and picturesque way in which Medieval theologians engaged maternal images of God is clear evidence that modern complementarians “have gotten Paul wrong”—except in the places where he was wrong (53, 35).

She feels confident in this as indicated by her oft-displayed tour de force, “Because I am a historian, I know there is more to Paul’s letter than what his words reveal” (56). Barr revels frequently in the advantage she has in exposition because of her knowledge of women in Medieval history. She finds Margery Kempe particularly compelling because she reprimanded the Archbishop of York as a wicked man and because she would rather see her husband “decapitated by a murderer than sleep with him again” (73, 75). Also, she received a special revelation from God of assurance for heaven accompanied by “the blessed Mother . . . St Katherine, St Margaret and St Mary Magdalene” (76; also 168, 181, 183).

She feels confident in this as indicated by her oft-displayed tour de force, “Because I am a historian, I know there is more to Paul’s letter than what his words reveal” (56). Barr revels frequently in the advantage she has in exposition because of her knowledge of women in Medieval history. She finds Margery Kempe particularly compelling because she reprimanded the Archbishop of York as a wicked man and because she would rather see her husband “decapitated by a murderer than sleep with him again” (73, 75). Also, she received a special revelation from God of assurance for heaven accompanied by “the blessed Mother . . . St Katherine, St Margaret and St Mary Magdalene” (76; also 168, 181, 183).

Barr’s decision to challenge complementarian teachings in her church came “Because I am a medieval historian” (72). She is thankful for the Protestant Reformation, but “as a historian, I know these changes came with a cost” to women (107, 127); “as a historian, I know that all biblical translations are shaped by human hands” (130); “as a medieval historian, I know that Christians translated Scripture in gender-inclusive ways long before the feminist movement” (133); to the traits of biblical womanhood delineated by Nancy DeMoss Wolgemuth, she approved Randall Balmer’s historical judgment that that profile “is nothing more than ‘a nineteenth-century construct’” and for herself she asserted, “To my women’s history-trained ears, these words might have come straight from the Enlightenment writings of Rousseau” (171); or in referring to women who reported evangelistic success in preaching she commented, “Because we lack a historical context in which to evaluate Piper’s claims, evangelicals accept his teachings” (181); “By forgetting our long history of women in public ministry . . . evangelicals moved closer to making biblical womanhood gospel truth” (186); “As a church historian, I immediately recognized the eternal subordination of the Son as Arianism” (194).

That Barr has a penchant for getting both theological and exegetical hints from history certainly is a healthy propensity. I do the same and encourage my students to reflect historically on current ideas. Some theological issues are given clear construction in the context of historical polemics we do not need to refight, though we need to claim them with conviction. An evangelical, however, would never encourage any student to use historical narrative as a canon by which the plain meaning of a text of Scripture may be ignored or relativized into meaninglessness. Scripture, as a revelation from God and thus infallible, and thus inerrant, is the final, and only, authority in any matter concerning faith and practice, belief and conduct. This is particularly relevant to one’s understanding of Paul’s meaning in 1 Timothy 2:11ff for he relates his instructions specifically to behavior “in the household of God, which is the church of the living God, a pillar and buttress of the truth” (1 Timothy 3:15).

It is surprising that in her just confidence as a historian she would still confess as a former delusion that she “honestly thought inerrancy was a Baptist idea.” Someone taught her, however, that the “Calvinist theologians at Princeton Theological Seminary actually led the inerrancy charge” (189). Perhaps not as serious as her disdain for the deadly trifecta of Calvinism / Inerrancy / Complementarianism but equally as delusive is the idea that Baptist views on inerrancy were dependent on the so-called Princeton Theology. That has been demonstrated as utterly unfounded.

In her experience, “inerrancy creates an atmosphere of fear. Any question raised about biblical inerrancy must be completely answered or completely rejected to prevent the fragile fabric of faith from unraveling.” Complementarianism as a necessary conclusion from a commitment to inerrancy was “the biggest lie of all” (204). In reality, she contends, complementarianism on this basis has been the enzyme through which misogyny and abuse have grown and even been defended in the church. “We have allowed teachings to remain intact that oppress women and stand contrary to everything Jesus did and taught” (8). “Everything?” Careless language for a careful historian.

A bizarre notion arising from her penchant for the authority of history is the challenge to the words “wife” and “marriage” in biblical translations (148-150). This includes God’s creation of Eve from a rib of Adam; the insertion of wife and marriage were errors derived from modern notions—1611—even though “neither the word marriage nor the word wife appear in the Hebrew Text” (150). Early modern translations “added one more layer to the growing idea of biblical womanhood.” Could it be because Jesus, in referring to the text in Matthew 19:3-10 in using the word “woman” uses it as synonymous with wife?

In one sense, perhaps the dominant sense by her own admission, this book is about her—“This book is my story” (33). This makes a charming literary glue and carries along the story very well. Some of her most determinative convictions came as she ate alone at Chili’s, found herself flummoxed by a classroom event, washed the dishes, mowed the lawn, or went about daily tasks (26, 66, 70, 71, 201 et al.). Her life frames her argument—“This experience, along with my husband’s firing, frames how I think about complementarianism today” (204). Her husband was fired from a church position he had served in for fourteen years because he challenged the church leadership’s commitment to complementarianism—He disagreed with them, apparently under her influence, on their stance of “women in ministry” (3, 4). The second was what she called her “Me Too” admission (201-204), a particularly poignant experience with a boyfriend caused by the toxic effect of Bill Gothard’s Basic Youth Conflicts movement. She considers herself scarred by these two events in such a severe way that she “will always carry the scars.”

One driving theme she continues throughout the book is the idea of “patriarchy” and its shifting form adapting so well to the complementarian ethos. “Patriarchy is a shapeshifter—conforming to each new era, looking as if it has always belonged” (188). Evangelical complementarians have overtly called for the concept of patriarchy without realizing that they merely are perpetuating a purely pagan and secular concept thinking they conform to biblical truth (3-37). So powerful the idea became that one can detect its oppressive character “even to the writing of Paul” (35).

In the Reformation, “Instead of Scripture transforming society, Paul’s writings were used to prop up the patriarchal practices already developing in the early modern world” (123). For this reason, she recommended a rethinking of the entire corpus of Scripture, as suggested by Beth Moore, “and refused to let 1 Corinthians 14 and 1 Timothy 2 drown out every other scriptural voice” 217). Her own epiphany came, not from the biblical text, but “because the biblical text fit so well with historical evidence” (32). When she inferred Arianism from the idea of personal subordination of the Son to the Father, she observed that tat this constituted the “perfect prop for Christian patriarchy” (196).

Barr mutes present exposition of Scripture by a consistent appeal to medieval exegesis and practice. Though patriarchy still loomed large, medieval women were able to create pockets of freedom and a presence in teaching and preaching that was squashed by the Reformation. As she emphasized in her presidential address, “The focus on a handful of Pauline texts that today dominate how we as North American Christians think about women in the church is rooted in a historical moment.” These verses have not always been so important she concludes by a careful survey of medieval sermons and the confident operation of Medieval women (72-99). She probably is right and the same could be said about a multitude of other biblical passages and important doctrines using the same criteria. If medieval sermonic use of Scripture becomes the canon of interpretation, one would be hard pressed to argue that justification by faith on the basis of imputed righteousness is the Pauline and consistently biblical, presentation of how sinners will find acceptance with God on the day of judgment. Does the lack of consistent use in medieval sermons render irrelevant the careful attention given to a text in the twenty-first century?

Barr mutes present exposition of Scripture by a consistent appeal to medieval exegesis and practice. Though patriarchy still loomed large, medieval women were able to create pockets of freedom and a presence in teaching and preaching that was squashed by the Reformation. As she emphasized in her presidential address, “The focus on a handful of Pauline texts that today dominate how we as North American Christians think about women in the church is rooted in a historical moment.” These verses have not always been so important she concludes by a careful survey of medieval sermons and the confident operation of Medieval women (72-99). She probably is right and the same could be said about a multitude of other biblical passages and important doctrines using the same criteria. If medieval sermonic use of Scripture becomes the canon of interpretation, one would be hard pressed to argue that justification by faith on the basis of imputed righteousness is the Pauline and consistently biblical, presentation of how sinners will find acceptance with God on the day of judgment. Does the lack of consistent use in medieval sermons render irrelevant the careful attention given to a text in the twenty-first century?

The resuscitation of the accusation toward complementarians of Arianism shows how far she is willing to go in her personal quest for vindication. Two deeply disturbing difficulties surround this desperate attempt at discrediting complementarianism. One concerns the striking irony of the concern. She considers inerrancy dangerous, oppressive, and fearsome. Yet the rejection of Arianism and the assertion of the deity and consubstantiality of the Son is dependent on rigorous exegesis of the ipsissima verba of Scripture and application of carefully constructed vocabulary and phrases of Jesus. It looks to the internal doctrinal ideas within the canon of Scripture itself and imposes a deep mystery on the witness of the church—that there is one God, a radical monotheism, and yet this one God eternally exists in three personal subsistences, each person co-eternal and consubstantial with the other persons, each maintaining distinct personal properties. Each maintains eternally and infinitely the beauties and immutable traits of personhood as well as sameness in simple essence. This biblical doctrine depends on a rigorous commitment to the inerrancy of Scripture.

The second difficulty with the accusation is that it simply is not true. Dr. Barr cites approvingly the statement of Aimee Byrd her summation of the concept of the eternal subordination of the Son as saying, “The Son the second person of the Trinity, is subordinate to the Father, not only in economy of salvation but in his essence” (193). Barr looks at another statement on “authority and submission in the nature of the Trinity” and states her fear that many evangelicals have “converted” to complementarianism “without realizing that the eternal subordination of the Son is a teaching outside the bounds of Christian orthodoxy” (193).

One is tempted to engage the issue with a theological excursus (maybe I will succumb briefly to the temptation), but I will focus the response to a simple manifestation of the Christology of one of the leading complementarians. Wayne Grudem in his massive Systematic Theology begins his section on Christology with this definition: “Jesus Christ was fully God and fully man in one person and will be so forever” (663). He gives ample biblical proofs for the full manhood, of one nature with us sinners, sin only excepted, of Jesus. That is followed by the direct scriptural claims of the deity of Jesus and the evidence that Jesus possessed the “attributes of deity” including omnipotence, eternity, omniscience, omnipresence, sovereignty, intrinsic immortality, and worthiness of worship.

In summarizing all of these, Grudem concludes the “full absolute deity of Jesus Christ” (688). He affirms the symbol of Chalcedon concerning the fullness of two natures, human and divine, in one person and gives a lengthy biblical defense of Chalcedonian Christology (690-701). He closes the discussion with this summation: “It is by far the most amazing miracle of the entire Bible—far more amazing than the resurrection and more amazing even than the creation of the universe. The fact that the infinite, omnipotent, eternal Son of God could become man and join himself to a human nature forever so that infinite God became one person with finite man—that will remain for eternity the most profound miracle and the most profound mystery in all the universe” (700). True indeed, profoundly provocative of worship, and the antipodes of Arianism.

Eternal subordination of the Son of God, therefore, has nothing to do with Arianism, or Nestorianism, or Eutychianism. It is, moreover, an accurate statement of the eternal reality of three distinct personhoods within the single and simple essence of the One True God. This could not be called a miracle—like the incarnation fittingly is called—but an eternal reality undergirding the entirety of being, created and uncreated. If God is single and simple essence, then the co-eternality of three persons does not disturb it but helps with some degree of perception. If his simplicity means that there are no accidents in God, but all of his actions are consistent with his simplicity and essential oneness, then the voluntary submission of the Son to the Father in the incarnation does not reflect a temporary state but fits perfectly with and is an expression of the essential oneness of the Trinity.

The covenantal arrangement, therefore, of the Son to come as the Redeemer of creature-sinners in obedience to the will of the Father is fully consistent with how eternal personhood is characteristic of the simplicity of essence in God. When Jesus says (John 6:38, 39)—“I have come down from heaven, not to do my own will but the will of him who sent me. And this is the will of him who sent me, that I should lose nothing of all that he has given me, but raise it up on the last day”—he speaks of a covenantal arrangement made within eternity the execution of which cannot be in any sense a violation of the eternal relation between Father and Son. Nor is it an arrangement in tension with the way in which any person of the Trinity manifests this single will of redemption. To do the Father’s will—“on earth as it is in heaven”—defines an element of the perfect consonance of the Son and Father in will as well as essence.

When Jesus said, “I have come in my Father’s name,” (John 5:43) both the singularity of that will as well as the subordination of the person of the Son as a distinction of his personhood in relation to the person of the Father is a perfectly orthodox position and most fitting as a model for subordination without inferiority—subordination even in singularity of essence. It is not surprising if the first and primal human relation, that of husband and wife, should reflect that eternal relation. The accusation of Arianism based on eternal subordination of the person of the Son to that of the Father is an absurdity arising from unsound reflection on the mystery of trinitarian reality.

Barr has written an interesting and engaging book—clearly provocative of important discussion. She shows a dedication in research and teaching legitimately enviable by all church historians and admired by her students. The quest, however, to use this forum as a balm for personal healing has rendered her judgment erroneous in some vital places that severely compromise the validity of her conclusions.

Tom J. Nettles is retired professor of Church History at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary.