Reviewed by Greg Cochran

Introduction

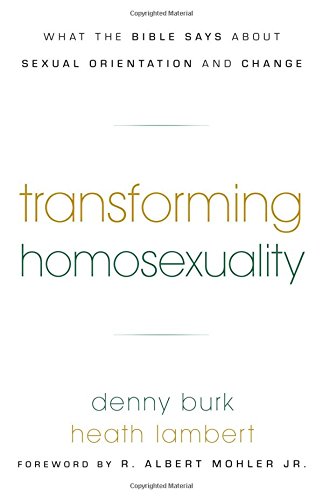

Many good resources concerning the Bible and homosexuality have emerged over the past five years. Two of the more popular volumes are Kevin DeYoung’s What Does the Bible Really Teach about Homosexuality? (Crossway 2015) and Sam Alberry’s Is God Anti-Gay? (Good Book Company 2013). Each of these books has proven to be helpful for Christians seeking better to understand our own faith and the ongoing war against sin. The thrust of these volumes is to understand the biblical position concerning homosexuality.

For authors Denny Burk and Heath Lambert, the time has arrived for moving the conversation another step forward. According to Burk and Lambert, evangelicals share a consistent conviction that homosexual practice is sinful according to the Scriptures. Division now is taking place at the level of attraction, desire, and temptation. The evangelical conversation must address whether or not same-sex attraction is sinful.

In their own description of this volume, P&R Publishing says, “Faithful Christians today agree that the Bible forbids homosexual behavior. But when it comes to underlying desires, the jury is out. Some Christians view homosexual desire as morally neutral, while others believe it calls for repentance and gospel renewal.” In his Foreword to the book, R. Albert Mohler agrees with this assessment: “Faithful Christians who struggle with these desires must know that God wants both their affections and their patterns of attraction reordered according to his Word… These are challenging theological issues and represent one of the urgent pastoral tasks of our time” (p. 10).

Summary

Burk and Lambert take up the challenge, hoping to offer a biblical and theological response to same sex attraction. After a brief explanation of why this book needs to be written, the authors divide the remainder of the small volume into two parts. Part One is called “The Ethics of Desire.” Part Two develops “The Path of Transformation.”

So why write another evangelical book addressing homosexuality? For these authors, the answer is to address a lacuna in the literature on the subject: “Our goal,” they say, “is not to consider again the ethics of homosexual behavior, but to consider the ethics of homosexual desire often referred to as homosexual orientation” (13). According to Burk and Lambert, the verdict is settled concerning homosexual activities. What is left to discuss and hopefully settle is whether homosexual desire (or attraction) is also sinful. Ultimately, these authors hope to affect change—not merely behavior change, but complete personal transformation through the power of the gospel.

The next two chapters focus on Same-sex attraction: what it is and whether it is sinful. Before establishing a definition for same-sex attraction, the authors let the readers know they are drawing from the definition employed by the American Psychological Association (APA). Indeed, they offer four disclaimers about using a secular definition before they offer the definition itself.

Once they put forward the APA definition for sexual orientation, Burk and Lambert then categorize (according to various views of Scripture) the other Christian attempts to provide definitions for orientation and attraction. The four categories used are liberal, revisionist, neo–traditional, and traditional. The first two categories are ruled inadequate, while the third (neo-traditional) is considered to be an attempt at biblical fidelity, but still wrong. The fourth category—Traditional—is the category the authors place themselves in and offer full-throated support for addressing same-sex attraction.

The traditional view advocated in the book insists that both homosexual behavior and homosexual desires are sinful. The authors include the emotional and romantic aspects of attraction as well as the sexual desire. The question which arises, then, is whether same-sex orientation is also sexual attraction. For Burk and Lambert, the answer is yes: “A person is not absolved of an immoral sexual desire simply because it seems to follow an enduring pattern—i.e., an orientation” (29). The authors defend their belief from the Scriptures and the reformed tradition going back to Augustine on original sin: “We are sinful not only in our choices but also in our nature” (31). The conclusion to their defense is this: “To the degree that same-sex bonds are defined by sexual possibility and intention, they are sinful” (34).

Finally, the chapter concludes with a discussion of whether sexual orientation can or should be a consideration in personal identity. Burk and Lambert agree with Rosaria Butterfield that “accepting sexual orientation as an identity-defining element of the human condition is foreign to Scripture—except as a feature of human sinfulness” (37).

Chapter two covers in more detail the question of whether or not same-sex attraction is itself sinful. The real strength of this chapter is displayed at two clarifying points related to a theology of desire. First, after labeling same-sex attraction under the rubric of temptation, Burk and Lambert explain the precise nature of Christ’s temptation for us. This explanation of Christ’s temptation leads to a further discussion of why our temptation is sinful where Christ’s was not. In short, our temptation is sinful because it comes from within us—from our inherently sinful nature. Christ’s temptation came at him externally.

The second display of strength in this chapter is the concluding section which offers pastoral help for counseling those struggling with same-sex attraction. Having built their case upon Scripture and a reliance upon Augustine, the authors assert that same-sex attraction is sinful if the attraction is sexual in nature, if it carries the potential of being sexually expressed, or if it is used as a primary identity marker. Because same-sex attraction is sinful, it can be battled effectively if the church identifies with those who are struggling (as fellow sinners being sanctified). Moreover, war can and should be waged against all indwelling sin, and the church should be the safest place for such a war to be waged.

At this point, the book shifts its emphasis toward transformation. Burk and Lambert begin chapter three with an annotated outline of several myths about changing same-sex attraction. First, they expose the myth that understanding the Bible’s ethical demands will lead to change. Change will not happen magically upon one’s understanding of the Bible, but it can in fact change if churches are committed to ministry.

The second myth—that change is impossible—is tackled head-on by a reaffirmation of biblical instruction and the introduction of several stories which illustrate how often change has occurred. The third myth is that change is harmful. This myth might be the most difficult to address. Bills have been passed in New Jersey and California outlawing attempts at “reparative therapy.” The perception has emerged which asserts that assisting people in changing their sexual orientation is dangerous. The authors point out, however, that the danger is with the lifestyle itself, not with those who are trying to help.

Myth #4 is that change requires heterosexual desire. The authors point out that heterosexuality is not the goal. What the Bible expects and demands is holiness. Myth #5 is that change happens without repentance. The authors point out that biblically the path to change is always repentance. Indeed, they reassert that repentance is the only path to change.

Chapter four offers a further detailing of the biblical path to change. Burk and Lambert offer five paths of change from Ephesians 5. The first path is to repent of hatred and pursue love (Eph. 5:1-2). The second path is to repent of covetousness and pursue gratitude (Eph. 5:3-4). The third path is to repent of sinful presumption and pursue discipleship (Eph. 5:5-8). The fourth path is to repent of sinful concealing and pursue open accountability (Eph. 5:11-14). And the fifth path is to repent of cold hearts and pursue singing to Jesus (Eph. 5:18-19).

The final chapter is an admonition for evangelicals to change. Our cultural context attempts to force us all into either a “tolerance” position or an “intolerance” position. Instead, evangelicals must speak the truth, speak the gospel, and speak with humility. In all things, our aim is love.

Greg Cochran is director of applied theology, the School of Christian Ministries, California Baptist University, and Review Editor for Ethics here at Books At a Glance.