A Brief Book Summary from Books At a Glance

About the Authors

Timothy McGrew serves as Professor and Chairman of the Department of Philosophy at Western Michigan University.

Paul K. Moser serves at Loyola University of Chicago as Professor of Philosophy.

K. Scott Oliphint is Professor of Apologetics and Systematic Theology, Westminster Theological Seminary, Philadelphia.

Graham Oppy is at Monash University as Professor of Philosophy.

Introduction

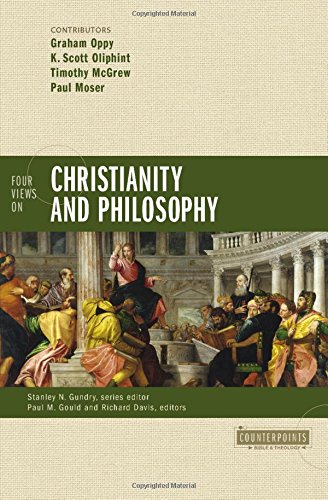

This book presents four different views on the relationship between Christianity and philosophy. The purpose of the book is to put four different views on the aforementioned topic into dialogue with defense and responses in order that the reader might see the merits of each case.

Chapter 1 presents the Conflict Model of Graham Oppy, which attempts to trump Christianity through the superiority of philosophy.

Chapter 2 focuses on K. Scott Oliphint’s Covenant Model, granting Christianity superior status over philosophy.

Chapter 3 is on Timothy McGrew’s defense of the Convergence Model, a view which posits that Christianity, which completes philosophy, is also confirmed by philosophy.

Chapter 4 reconceives all of philosophy in Christian terms as explained by Paul K. Moser.

Table of Contents

Introduction to Christianity and Philosophy: Four Views

Paul M. Gould and Richard Brian Davis

Chapter 1 – Conflict Model (Graham Oppy)

Responses

Rejoinder

Chapter 2 – Covenant Model (K. Scott Oliphint)

Responses

Rejoinder

Chapter 3 – Convergence Model (Timothy McGrew)

Responses

Rejoinder

Chapter 4 – Conformation Model (Paul K. Moser)

Responses

Rejoinder

Conclusion

Summary

Introduction to Christianity and Philosophy: Four Views Paul M. Gould and Richard Brian Davis

The relationship between Christianity and philosophy is difficult to articulate, especially given the difficulty of defining philosophy alone. However, an historical relationship exists between Christianity and philosophy, and philosophical reflection tends toward similarity with natural religious instinct, so the question of the relationship between Christianity and philosophy is deserving of greater focus.

Philosophy, which begins with a sense of wonder and means ‘love of wisdom,’ can lead to the vice of wishing to be known for wisdom, when faith must rest rather in God’s power. However, God is often seen as the ultimate object of wonder both in religious tradition as well as philosophical thought stretching back to Plato.

From Athens to Jerusalem and Back Again

At the Areopagus, the apostle Paul started a conversation between Christianity and philosophy that continued to develop through Tertullian, Origen, Augustine, Aquinas, and others leading up to the modern period which included René Descartes and Kant, followed by the philosophy of Jacques Derrida and postmodernism up to the current day.

Chapter One: Conflict Model

Graham Oppy

The contention of the Conflict View of the relationship between Christianity and philosophy is that metaphysical naturalism trumps Christianity, and that philosophical neutralism is consistent with both metaphysical naturalism and Christianity. Graham Oppy claims, “there are no merely philosophical worldviews.”

Christianity

If Christianity is religion, and philosophy is inquiry, then it is difficult to see how the two might relate, other than Christianity using the discipline of philosophy.

Philosophy

An important task of philosophy is evaluating worldviews.

Worldviews

Oppy takes Christianity to consist of a family of overlapping worldviews, where worldviews are complete in the abstract, but not in practice.

Two-Person Worldview Disagreement

Comparisons of worldviews may be construed in terms of a two-person disagreement, although it is noted this approach stands in need of adjustments.

Assessment

In a two-person worldview disagreement, worldviews should be evaluated in the articulation, internal, and external stages focused on the best versions of the worldviews in question.

Idealized Worldview Disagreement

Worldview disagreement should focus upon the best versions of the worldviews in question.

Naturalism

Christian worldviews cannot be compared with philosophy, which is not a worldview. Christian worldviews should not really be compared with non-Christian or atheist worldviews, as those worldviews have very little in common with one another apart from their denial of Christian worldviews.

Two Worldviews Compared

Naturalistic worldviews make better comparators, and are “ontologically and ideologically leaner” as exemplified through short discussions in sections on God, Trinity and incarnation, resurrection and atonement, miracles, afterlife, God as sustainer and provider, and an interim summary of the aforementioned topics.

Common Goals

Oppy argues for the superiority of naturalism, notes disciplinary differences Christianity and naturalism make when it comes to philosophy, and shuns the idea of bringing worldview specific presuppositions into philosophical discourse, but most importantly for the purpose of the discussion of the relationship between Christianity and philosophy, writes, “While philosophy may share some intellectual goals with Christianity and naturalism, philosophy is not a direct competitor with either.”

Common Means

Christianity and naturalism do share common intellectual means and goals.

Distinctions

Again, Christianity and naturalism are different because of their ontology and ideology. Philosophy has neither.

Central Questions

Philosophy is used to question Christianity and naturalism, but not the other way around.

Significance

While philosophy can make a theoretical difference to Christianity and naturalism, Christianity and naturalism make no difference to philosophy as a discipline.

Conflict Resolution

Although philosophy may be done from a Christian or naturalistic stance, in terms of worldview disagreement, philosophy does not allow presuppositions from Christianity and naturalism.

Concluding Remarks

Philosophy is neutral with respect to worldviews.

Response from the Covenant Model

K. Scott Oliphint

Oppy’s categories depend upon particular worldview presuppositions, dogmatically excludes Christianity’s explanation of everything at the outset, renders data meaningless apart from Christian principia, and conflates the necessity of agreement with the necessity of understanding for conversation and discussion.

Response from the Convergence Model

Timothy McGrew

Oppy’s appeal to simplicity is too simple, his appeals to other miracle accounts negligent of the details that lead to distinguishing the genuine from the counterfeit claims, and his treatment of the historicity of the resurrection of Jesus to be far too dismissive. McGrew rejects Oppy’s complaint about a lack of non-Christian testimony to the fact of the resurrection of Jesus, since those who believed in the resurrection of Jesus became Christians, and McGrew kindly refuses Oppy’s claim that naturalists and Christians might both be rational in holding their respective positions.

Response from the Conformation Model

Paul K. Moser

Oppy neglects a crucial distinction “between data had by a person and data agreed upon by persons.” Moreover, Oppy does not draw a distinction between justification a person can have even without being able to supply it in the social sphere.

A Rejoinder

Graham Oppy

Oppy believes Moser simply does not interact with the actual view he espouses. He allows one can be justified in believing in God apart from some sort of collective data that might justify belief in God, but the only collective data for God would then be the aforementioned claims to their knowledge of God. Oppy states what he believes to be a disagreement with Oliphint’s approach, “If we suppose that all that matters is minimizing ontological and ideological commitments, then we shall be nihilists: we shall suppose that there isn’t anything at all. And if we suppose that all that matters is maximizing explanatory breadth and depth, then we shall commit ourselves to a profligate panoply of explainers for what we would otherwise take to be mere coincidences.” Even though Oppy notes the broad brush nature of his initial argument, but takes his remaining space to reply to six critiques from McGrew concerning details related to miracles and the resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Chapter Two: Covenant Model

K. Scott Oliphint

Philosophy is the study of the natures of reality, knowledge, and right and wrong, and he understands Christianity to include the foundations of Reformation theology expressed in historic creeds and confessions. Two implications of Oliphint’s view of philosophy and Reformation theology are that the view is not his alone, and any philosophy aimed at truth necessitates theology such that Christianity “trumps” philosophy.

Foundations

Two principia, or foundational first principles, the principum escendi, which refers to the foundation of being, and the principium cognoscendi, which refers to the foundation of knowledge, are found in the discipline of theology. The principia of theology differ from that of other disciplines because they undergird the principia of those disciplines and are themselves from an outside source, “the existence and nature of God, and the doctrine of revelation (both general and special).” God is known by his revelation, his knowledge being archetypal while human knowledge is ectypal, such that God must reveal himself to us if we are to know him or anything else.

Covenant Foundations

In covenant, God willingly condescends in order to relate to his creation and its apex, humans, who are created in his image. Every person is related to God by way of covenant in Adam or in Christ.

Faith and Reason

The covenant model is incompatible with the conflict model, although both utilize faith and reason. In the covenant model, enlightened reasoning understands its place in a ministerial rather than magisterial function when it comes to thinking through the “consistency and coherence of God’s Word and world.”

Faith and Philosophy

If the foundation for philosophy is itself, then the authority of philosophy is found in unfounded logical laws. Meanwhile, theology posits God and his revelation as the foundation for philosophy, such that “it is theology that sets the boundaries and the parameters, the rules and the laws, for all other disciplines.”

Four Faults

One must, however, recognize boundaries to theology and philosophy. Philosophical principles cannot rule out the principles of theology, since the former is grounded in the latter, nor should philosophical principles which contradict theology be brought into theology. Philosophy must be viewed as a servant, not ruler, of theology. Finally, philosophical terms can often conceal theological error.

Covenantal Philosophy

With some minor qualifications, Alvin Plantinga expresses well the conclusion and application of the covenant view. Christians should be especially concerned with philosophical topics that pertain in particular to the Christian community.

Response from the Conflict Model

Graham Oppy

Oliphint’s six major claims are inconsistent with each other, and Oliphint’s principia are reducible to axioms, which are not the basis for any discipline, nor are there any transcendental foundations for any disciplines. Since God does not exist, neither do his revelation, nature, or role in our knowledge. Since natural reality is itself necessary, there is no disagreement between theists and naturalists regarding the intrinsic existence in the source of existence. There is, further, a distinction between skepticism and reasonable disagreement, as well as between laws of logic and laws of inference. There is no sense in which authority is held by any philosophers, and “The boundaries of philosophy are not determined by reason; rather, those boundaries are determined by the questions for which we know how to produce agreed answers using agreed methods.”

Response from the Convergence Model

Timothy McGrew

The trouble with defining Christianity as Reformation theology is that Reformation theology did not come around until the 16th century. Objectivity is possible, and though not everyone always follows evidence where it leads, the evidence still points in a particular direction. First principles do not accomplish the work Oliphint needs them to accomplish, as the eventual breakdown of Aristotle’s own. . .

[To continue reading this summary, please see below....]The remainder of this article is premium content. Become a member to continue reading.

Already have an account? Sign In