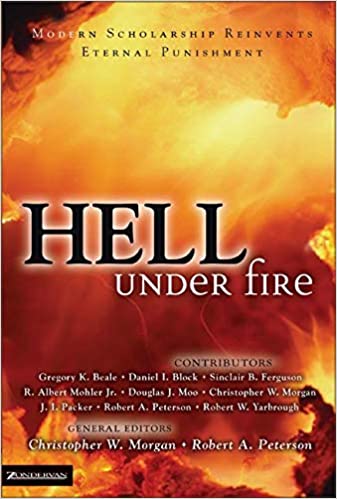

A Brief Book Summary from Books At a Glance

By Mitch Chase

Overview

Hell is under fire in evangelicalism. Interpreters who find the notion of hell distasteful have suggested annihilationism or even universalism as alternatives to the historic teaching of the church. But if the Scripture teaches what has indeed been the historic understanding of hell—as a divine punishment consisting of endless suffering on unbelievers—then Christians must be truthful, compassionate, and urgent with the lost.

Table of Contents

Introduction, by Christopher W. Morgan and Robert A. Peterson

1 Modern Theology: The Disappearance of Hell, by R. Albert Mohler Jr.

2 The Old Testament on Hell, by Daniel I. Block

3 Jesus on Hell, by Robert W. Yarbrough

4 Paul on Hell, by Douglas J. Moo

5 The Revelation on Hell, by Gregory K. Beale

6 Biblical Theology: Three Pictures of Hell, by Christopher W. Morgan

7 Systematic Theology: Three Vantage Points of Hell, by Robert A. Peterson

8 Universalism: Will Everyone Ultimately Be Saved?, by J. I. Packer

9 Annihilationism: Will the Unsaved Be Punished Forever?, by Christopher W. Morgan

10 Pastoral Theology: The Preacher and Hell, by Sinclair B. Ferguson

Conclusion, by Christopher W. Morgan and Robert A. Peterson

Book Summary

Chapter 1: Modern Theology: The Disappearance of Hell, by R. Albert Mohler Jr.

Though a fixture in Christian theology for many centuries, the historic teaching about hell basically disappeared during the 20th century. The historic Christian teaching about hell developed in the earliest centuries of Christian history and was based on Scripture. Hell was the eternal justice of God upon those without faith in Christ. Early evangelists and preachers in church history proclaimed the doctrine of hell and warned unbelievers of this coming reality.

In 553, the Fifth Ecumenical Council (Constantinople II) condemned Origen’s teachings of universalism, arguing that those who deny the eternality of hell would be anathema. Nevertheless, in the Middle Ages and Reformation periods, some sects and heretics still rejected the historic teaching of the church on this matter. And by the end of the 20th century, fear of eternal judgment had significantly diminished. Today few congregations hear the graphic warnings about hell which the Bible records.

The 17th century was a time of theological opposition to the historic teaching about hell. Socinians believed that eternal torment was actually unjust and that such torment was inconsistent with the character of God. English Arians and Platonists affirmed this logic. The 18th century was filled with Enlightenment skepticism, a posture that undermined any notion of eternal punishment. Some philosophers rejected Christianity as a whole, aiming their attacks more broadly than the doctrine of hell.

The Victorian era was characterized by church attendance, but this truth did not necessarily imply sound doctrine in those churches. Societal elites rejected the traditional doctrine of hell. This then became the legacy for the following twentieth century. Contemplating eternal punishment was met with revulsion. A vision of sentimental fatherhood was applied to God, and eternal torment in hell became simply unthinkable.

In the 20th century, Bultmann’s project of demythologization meant that hell should not be seen as a legitimate threat and literal place. Atrocities in the early decades of the 20th century represented hell on earth. Karl Barth had hope that God’s victory would bring universal redemption. Some theologians, such as Reinhold Niebuhr, saw hell in social travesties and inequities. Economic powerlessness needed liberation.

Despite how many professing Christians changed their minds on the doctrine of hell over the centuries, evangelicals continued to believe and preach the historic teaching on eternal punishment. People like John Wenham, near the end of the 20th century, acknowledged personal struggles with the idea of eternal punishment, the notions of which present such a formidable theological obstacle that, for him, it could not be overcome. Then John Stott, one of the most important evangelical leaders in the 20th century, reassessed hell and argued for annihilationism.

Chapter 2: The Old Testament on Hell, by Daniel I. Block

The Old Testament has little to say about hell. To begin such a discussion, readers should be aware of key Old Testament words and concepts about death and where the dead go. The abode of the dead is often called “the grave.” The word “pit” is sometimes used to refer to the place of the dead, and “the trap” denotes the idea of a pit for the dead. The word “earth” can sometimes refer to the netherworld, the land of the depths where the dead reside. According to some interpreters, Sheol refers to the grave, while others believe it is the netherworld. The term “mot” can sometimes refer to the place of the death, and even a power behind death (like Mot of the Ugaritic texts). Abaddon is the place of destruction, and it is the most negative expression for the place of the dead.

Inhabitants of the netherworld are called sometimes “the dead” and other times “the shades.” Ezekiel uses multiple expressions unique to his book, such as “those who go down to the Pit.” The Old Testament vocabulary suggests that Israelites shared with their ancient Near Eastern neighbors a three-tier view of existence: heaven was the realm of deity, earth was the realm of the living, and Sheol was the realm of the dead. Death on earth was viewed as sleep, though not “soul sleep” but sleeping in death here in order to awake in another world.

What was the state of the dead who enter the next world? The Old Testament is not monolithic in its answers. Some texts seem to present death as the termination of existence, and some characters (like Job) may long for death in order for their suffering to cease. But Ezekiel (in chapter 32 of his prophecy) portrays the state of the deceased in Sheol as conscious and as aware that their presence in Sheol was due to preceding acts done while alive on earth.

The general message of the Old Testament is the conviction that the dead continue to live after death. Because Hebrew anthropology taught that man was a unity, the end-time resurrection of the body is a reasonable hope due to the disembodiment that occurs at death. Regarding the afterlife as a place of eternal torment, the texts Isaiah 66:24 and Daniel 12:2 speak to this seldom-mentioned reality. Daniel 12:2 specifically prophesies the resurrection of the wicked for judgment. The expressions “eternal” life and “eternal” disgrace occur together in the Old Testament only in Daniel 12:2. Before Daniel 12:2, there is no clear evidence in the Old Testament for a belief in an eternal hell. . . .

[To continue reading this summary, please see below....]The remainder of this article is premium content. Become a member to continue reading.

Already have an account? Sign In