A Brief Book Summary from Books At a Glance

By Nathan Sundt

About the Author

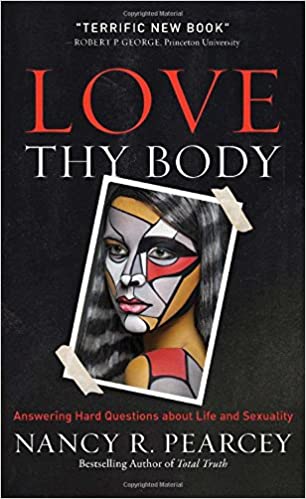

Nancy R. Pearcey has been hailed in The Economist as “America’s pre-eminent evangelical Protestant female intellectual.” A bestselling author and speaker who serves as professor of apologetics and scholar in residence at Houston Baptist University, Pearcey is also editor at large of The Pearcey Report and a fellow at Discovery Institute’s Center for Science and Culture.

Overview

Particular moral conflicts might characterize entire epochs, and Nancy Pearcey’s book Love Thy Body addresses this age’s urgent array of issues: “Human life and sexuality have become the watershed moral issues of our age.” Controversy surrounding life and the body find Christian dissenters labeled as hateful or hypocritical, even by bodies so eminent as the Supreme Court in its 2013 Windsor ruling and the US Commission on Civil Rights. Pearcey’s book also aims inward, at churchgoers; she states disturbing numbers related to pornography, cohabitation, divorce, homosexuality and transgenderism, as well as abortion within the ranks of those who attend church regularly. To evangelize the unbeliever or disciple the believer, Pearcey shows that a secular morality “doesn’t fit the real universe.”

Pearcey sets forth her most common analytical tool, adapted from her teacher Francis Schaeffer—the notion of a two-story split, which reveals how the modern mind separates (and has trouble re-integrating) theological or moral claims with scientific claims, private claims with public. Related to her present subject matter, the split separates values (in the “upper story” of thought) from facts (in the “lower story” of thought). “This two-story division equips us with a powerful new strategy for helping people see why a secular ethic fails, both personally and publicly.” Indeed, Pearcey aims not precisely to provide another biblical-theological monograph, nor another natural-law argument per se but to show how the new moral order fails its practitioners—how these new moral maxims hate, rather than love, the body.

Table of Contents

Introduction

1 I Hate Me: The Rise and Decline of the Human Body

2 The Joy of Death: “You Must Be Prepared to Kill”

3 Dear Valued Constituent: You No Longer Qualify As a Person

4 Schizoid Sex: Hijacked by the Hookup Culture

5 The Body Impolitic: How the Homosexual Narrative Demeans the Body

6 Transgender, Transreality: “God Should Have Made Me a Girl”

7 The Goddess of Choice is Dead: From Social Contract to Social Meltdown

Book Summary

Chapter 1: I Hate Me: The Rise and Decline of the Human Body

Pearcey employs human interest stories to show persons whose lives “run up against the wall of reality,” persons such as a liberal feminist British broadcaster who, when pregnant, began calling the life a “baby” because she wanted it—all the while knowing that if she did not want it she would call it “a clump of cells.” Pearcey documents how this woman’s view came to admit that the human life starts at conception but how, perhaps until the life “grows enough,” it hasn’t really become “a person.” For this reason, Pearcey emphasizes how such an approach to life is “radically fragmented, fractured, dualistic.”

In ordinary language human being is the same as person. “The two terms were ripped apart by the Supreme Court in its 1973 Roe v. Wade abortion decision, which ruled that even though the baby in the womb is human, it is not a person under the Fourteenth Amendment.” Pearcey concludes: “Thus we have a new category of individual: the human non-person.” The recognized biological organism that begins at conception, therefore, is expendable and occupies the lower-story of her schematic. By contrast, the Christian worldview unites the worth of body and person and establishes the value of nature in the will of the Creator. “If nature is teleological, and the human body is part of nature, then it is likewise teleological.” The Christian view respects the goals and orientation of nature.

Pearcey points to the dynamics of modern Darwinism and materialism to explain how the West lost this “purpose-driven view of nature.” Pearcey calls this two-story approach “personhood theory” where the biological organism has no intrinsic purpose and personhood is an achievement of “consciousness, self-awareness, autonomy, and so on.” If this worldview does not consider the body enough to establish worth at life’s beginning, nor can it establish such value at life’s end—a point that Pearcey exemplifies through the 2005 Terry Schiavo case.

Pearcey argues that certain conditions of personhood emerge, while those who do not meet such conditions are “demoted to non-persons. And a non-person is just a body—a disposable piece of matter, a natural resource that can be used for research or harvesting organs or other purely utilitarian purposes, subject only to a cost-benefit analysis.” She is careful to point out that her analysis does not focus on an individual’s feelings regarding abortion or euthanasia but about the “logic implied by the act itself.” The actions “imply a two-story worldview that is dehumanizing—one in which humans do not have rights, only persons do.”

As Pearcey turns towards the Christian response, she highlights how scripture “gives the intellectual resources to answer any question with confidence” and how the “Bible’s positive message . . . must be communicated not only in words but also in behavior by treating everyone with dignity simply because they are made in God’s image.” The personal starting point is “compassion for people trapped in a dehumanizing and destructive view of the body.” The intellectual starting point “is a biblical philosophy of nature,” in which the material realm has value and dignity bestowed by its loving Creator. “Respect for the person is inseparable from respect for the body.”

For Pearcey, “the body is the only avenue we have for expressing our inner life or for knowing another person’s inner life.” Pearcey asserts that “the Bible does not separate the body off into a lower story, where it is reduced to a biochemical machine. Instead, the body is intrinsic to the person.” This “incarnational ethic was radically different from the Gnostic tendencies in which the earliest Christians found themselves but based historically on the pronouncement of “very good” that God made in Genesis. Further, the incarnation of the Word established firmly in the Christian mind the value and dignity of the body, while the doctrine of the resurrection and ascension curtail any Gnostic thought that Jesus “escaped” the body. Rather, the salvation he made in the body is for the bodies of men and women.

“Because [Jesus] was taken bodily into heaven, this human nature is permanently connected to his divine nature.” Last, Pearcey highlights how Christ’s second coming guarantees the defeat of death. “Christians are never admonished to accept death as a natural part of creation.” “Jesus’s resurrection is an eloquent affirmation of creation …. The Bible teaches an astonishingly high view of the physical world.” Citing the work of N. T. Wright, Pearcey notes how Gnostics perverted Christian teaching and, like in our own day, “a privatized, escapist, other-worldly spirituality was far more socially acceptable.” Gnostics did not suffer the same persecution as Christians, she argues, due in part to the fact that their view of the body had not the social and political implications as the Christian view did.

Chapter 2: The Joy of Death: “You Must Be Prepared to Kill”

Pearcey points to the obvious biological fact that anything intrinsic to the nature of an organism is present from fertilization. Returning to her term “personhood theory,” Pearcey identifies how in the literature humanity and personhood are separated. (She cites Hans Küng, who says the embryo is human but not a person; Peter Singer, who says that the life of a person does not begin as early as the life of a human organism; and even Justice Harry Blackmon, who wrote in the Roe v. Wade decision that the word person does not include the unborn.)

Pearcey then sketches how Plato in the ancient world and Descartes in the modern world separated the human body and mind. In particular, she argues, Cartesian dualism, having separated the human person into two entirely different substances, helped create this two-story logic whereby a human organism might be denied personhood. “At least since Descartes, the mind has been regarded as the authentic self.” Thus, the body, by definition, is “sub-personal.” Pearcey evaluates the arguments ethicists make for what qualities do establish personhood. She notes that (1) such ethicists do not agree on the qualities, (2) most candidates for these qualities become highly problematic when we consider persons who suffer from mental retardation or other handicaps, (3) and none of these qualities provide a time in the birthing room or nursery that establishes the baby’s personhood.

[To continue reading this summary, please see below....]The remainder of this article is premium content. Become a member to continue reading.

Already have an account? Sign In